Bushfires to Covid-19: What makes a good leader in a time of crisis?

Out of the ashes of the bushfire crisis to the Covid-19 pandemic, a new style of crisis leadership has emerged.

Penned by independent economist Stephen Koukoulas and ASX-listed AI company Flamingo Ai founder Dr Catriona Wallace, this is the first of a two part article analysing Australia’s crisis leadership during two of the worst natural disasters in history. Read part two here.

A Story of Crisis

In early January 2020, with my sister Kirstie, I drove to our family beach house at Rosedale, built over 60 years ago by our grandparents, Norm and Eileen.

Rosedale got torched on New Year’s Eve.

It was an apocalypse.

We were however prepared for the devastation having watched our 10,000 acre family farm near Wingham be incinerated by the fires in November.

We know what a crisis looks like, what it smells like, what it feels like.

It’s like a war zone.

As we drove into the village of Rosedale on this hot, dry January afternoon, we turned into Paul St, and saw our neighbour’s house burned to the ground – the ember attack took 15minutes to consume their house.

We drove past a hand-made sign ‘Night Patrol Active’ which we learned referred to the neighbours taking shifts to patrol the streets at night for spot fires and looters.

The fires from our three neighbours’ houses, all burned, tore up to our walls on all sides, melted the taps, the pipes, a fly screen door – but did not burn the house. We were the lucky ones.

It did not burn because the neighbours, Gordon and Rodney, stood between the fire and our house and fought it back. We had never met either Gordon or Rodney before. They risked their lives for us; complete strangers.

I still have a thousand uncried tears. As I know many of you have. And burned into our shared psyche is:

46million acres (19m hectares) of land incinerated

34 people dead

More than 1 billion animals dead

6,000 buildings destroyed

306 million tonnes of CO2 released to the atmosphere

Aboriginal rock art and other sacred sites destroyed

Damage of over $5bn in lost revenue to businesses

We had a crisis of the most extreme kind and the question on many minds was - who were the “crisis leaders” and what should they have done?

What is ‘crisis leadership’?

Crisis Leadership is described as the ability to direct and effectively reduce the duration and impact of extreme situations. It focuses on multi-level strategy with multi-level contingencies and communications, clarity of vision, explicit and actioned values, effective logistics and building empathy and caring relationships.

A Crisis Leader is someone who leads others through a sudden and largely unanticipated negative and emotionally draining circumstance. The Crisis Leader has the job of protecting lives, jobs, creating organisational resilience and managing public opinion.

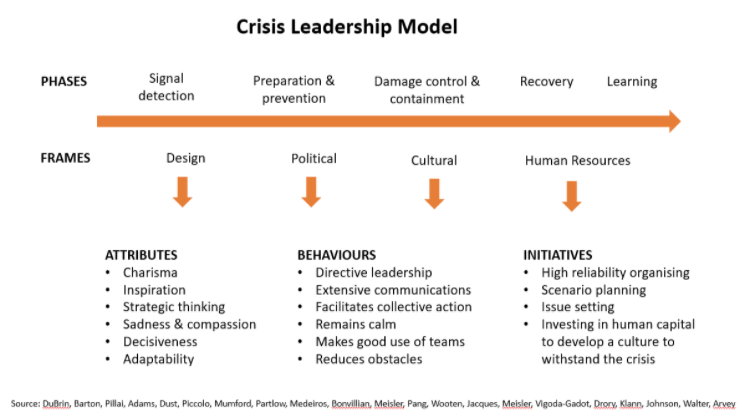

A model of Crisis Leadership may have the following characteristics:

Figure 1: Consolidated Crisis Leadership Model

In order to assess how effective Australian leadership was during the Summer of 2019 crisis, we examined leadership of the key events.

Leadership before, during and after the fires

The Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, and the Federal Government had the opportunity to lead this crisis well before it started, to detect signals, prepare, prevent, contain, control then recover. Below, the crisis timeline and key events related to the fire are mapped against the Crisis Leadership Model phases:

Phase 1: Signals

Australia had experienced record breaking drought conditions, 36 months of above average temperatures and a consistent decrease in annual rainfall since 1990.

In April 2019 former Fire Commissioners warned the Federal Government that “the country is not prepared for the fire danger posed”; in November 2019 Indigenous fire practitioner Victor Steffensen stated, "Jump in the passenger seat, and let us drive for a change".

Unfortunately, signals were not heeded by the Federal Government and little action was taken.

Phase 2: Preparation and prevention

The bushfires started on September 6th 2019 but it was not until December that the New South Wales Government declared a State of Emergency. On December 5th, the military were deployed to help however only with logistics. In December the Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, travelled to take a holiday in Hawaii and the Minister for Emergency Services, David Elliott, took a vacation to Europe. The Government was not prepared and little prevention was in place. Politicians were missing in action.

Phase 3: Damage control and containment

On December 31 a Chinook and Spartan military aircraft were finally deployed for sea evacuations along with 2 naval vessels. On January 4th there was a meeting of the National Security Committee and there was a compulsory call out of Army reserve brigades – 3000 personnel. On January 4th the first proper fire-bombing planes were leased. On 31 January, the Australian Capital Territory declared a state of emergency in areas around Canberra. The fires were not controlled, and most were not contained. The fires did not end until the rains of February 2020 fell.

Phase 4: Recovery

On January 6th, exactly 4 months after the fires started, the Government announced a National Bushfire Recovery Agency - $2bn under the control of the head of the Australian Federal Police, Andrew Colvin; in January 2020 the military were mobilised to assist in recovery. The government did step up its involvement during the early stages of the recovery phase and was more visible and effective at this stage.

This analysis suggests that the Government did not perform well as Crisis Leaders during the signal, prepare and prevent, damage control and containment phases, however, did improve performance in the recovery phase. The final phase, learning, has just commenced.

The overriding factors that drove the Federal government’s lack of performance as crisis leaders appears to have been driven by political, financial and organisational influences. These included:

the lack of acknowledgement of climate change driven by political interests

the influence of the powerful interest groups such as the mining sector

the inability to organise, finance and mobilise appropriate responses to the crisis

The question then arises - who did perform well as Crisis Leaders? To find this out, a survey of 15 residents of Rosedale was conducted.

Crisis leadership: Rosedale residents’ view

The study of the Rosedale residents, directly affected by the fires, reveals that they are emotional, traumatised and angry and have been severely negatively financially impacted by the crisis.

Quotes such as “Coalition leaders denying climate change, going on holidays and showing disrespect to victims” were common with most residents believing that climate change was ignored by the government and the country suffered as a result.

Overall, 89 per cent believe that the politicians and federal government were “not at all effective” in reducing the impact of the crisis before, during and after the fires, citing lack of knowledge, accountability, receptiveness and learning from the Prime Minister.

What did we learn?

The noun ”crisis” comes from the latinised form of the Greek word ‘krisis’, meaning ‘turning point in a disease; a point at which change must come.’ Similarly, the derivation of the word ‘apocalypse’ means ‘an unveiling’.

So, what did we learn and what was unveiled during the summer of 2019?

We learned that leadership at the most senior levels did not adhere to best practice crisis leadership models, attributes or behaviours.

Evidence suggests that the leaders denied facts, did not consult with experts, were not prepared, could not contain the situation and prioritised political and image related agendas. The result was mass devastation on a scale not seen before in this country.

However, at State and local levels, with exemplars like NSW Premier, Gladys Berejiklian, Victorian Premier, Daniel Andrews, NSW Member for Bega, Andrew Constance and the NSW Fire Commissioner, Shayne Fitzsimmons we did see evidence of effective crisis leadership.

The behaviours displayed by these people included: strategic thinking, political agenda management, wide consultation, decisiveness, adaptability, sadness and compassion and inspiration.

Importantly we also saw great vulnerability shown by Andrew Constance as he talked about his own mental and emotional anguish.

Local crisis leadership was also effectively shown by ordinary Australians, like the fire service, the volunteers who put their lives on the line and Rosedale’s Rodney and Gordon.

Enter coronavirus and a call to action for a new Crisis Leader

On the back of the fire crisis has come a new crisis. As at March 2020, there are 130,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 or Coronavirus, globally, the world is going into lockdown and the economy has been hit hard. This multi-crisis mode demands that a new leadership model emerges.

Based on what we have learned, out of the ashes, comes a revised model of crisis leadership behaviour that ideally will position our leaders better to handle new crises, including COVID-19 and others that will most certainly come:

Figure 2: Out of the Ashes: A New Model of Crisis Leadership Behaviour

Whether dealing with an environmental, social, health, economic or organisational crisis, through leaders displaying the behaviours outlined in this model, we should have great hope that crises could not only have their impact minimised, they could be avoided altogether.

The hope new leaders will emerge

On a personal note, as a result of the fires on our family farm, the cost of feeding the cattle is untenable. We now must sell the herd and significant parts of the farm to cover costs. We have laid off the workers and the farm’s business will end.

As heartbreaking as this is, we still feel hope. The rains have come, the dams are full, and the grass is green. We will look to our Indigenous communities for advice on healing and regenerating the land and will commence a project on using artificial intelligence to develop fire-fighting robots.

We also have great hope that leaders will emerge who will be competent signal detectors, political agenda managers, can set issues and mobilise collective action, who use data-driven critical thinking and advanced technology and who understand multi-cultural and stakeholder lenses.

These leaders can be vulnerable, highly empathetic and will create a vision that people will follow out of crisis.

All of these skills are now required as we face into the next crisis – coronavirus and its deep impact on the economy.

Dr Catriona Wallace is the Founder of Artificial Intelligence and ASX Listed company Flamingo Ai and has a PhD in Leadership. Flamingo Ai is the second only woman led (CEO & Chair) business to list on the Australian Stock Exchange. Dr Wallace is Adjunct Professor at the AGSM, UNSW and sits on the Board of Responsible Technology Australia.

Make your money work with Yahoo Finance’s daily newsletter. Sign up here and stay on top of the latest money, news and tech news.

Follow Yahoo Finance Australia on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance