Life-threatening feature of common garments exposed

Ill-fitting workwear not only alienates women in construction jobs, but can also be potentially life threatening, a new report has found.

Related story: ‘Grossly unfair’: How Australia’s super system penalises mothers

Related story: How Aussie mum designed an Uber for women

Related story: Why 2019 has been the worst year in a decade for women on boards

The Bisley Workwear Tradies Report 2020 found that workwear designed for men’s bodies can place women wearing it on worksites in danger, with 60 per cent of women surveyed having worn workwear designed for men.

And, 40 per cent of female tradies reported feeling less safe at work, due to the garments. On top of that, 45 per cent say the garments make them feel they don’t belong.

Bisley Workwear owner David Gazal said the study highlighted the number of women in the infrastructure, mining and construction sectors affected by ill-fitting garments. The study comes as Bisley announces its new launch of workwear tailored for women’s shapes.

But it’s not just workwear potentially placing women’s lives at risk.

Stab-proof vests, medicine and even air conditioning designed with men in mind

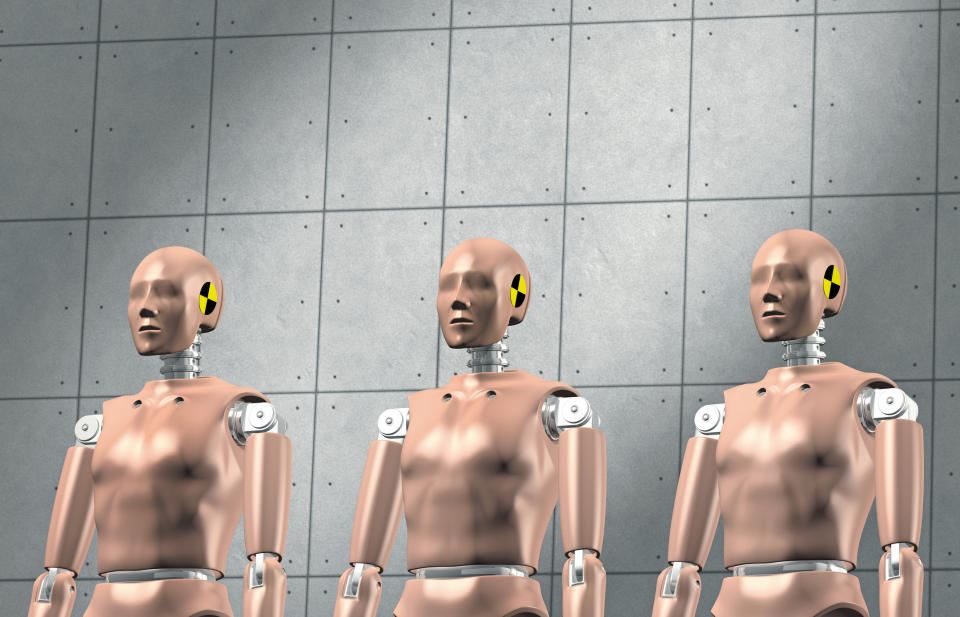

The design of stab-proof vests and car crash dummies has historically been based on men’s bodies, author Caroline Criado-Perez highlighted in The Guardian in 2019.

And a study from Consumer Reports released in October 2019 also highlighted how male-focused crash test dummies place women’s lives at a greater risk.

“An average adult female crash test dummy simply does not exist, despite the fact that women obviously drive to work, take road trips, and ride in cars with friends, and even though female bodies react differently from male bodies in crashes,” that report found.

“That absence has set the course for four decades’ worth of car safety design, with deadly consequences.”

Women are 17 per cent more likely to be killed in a car crash than a man of the same age, and a woman wearing a seatbelt still has a 73 per cent higher odds of becoming seriously injured.

There’s even a gender gap in health: the Medical Journal of Australia in November last year released a report finding health data has historically been collected for men, and then generalised to women.

“Failure to appreciate the differences between and across the sex and gender spectrum risks compromising the quality of care and increasing costs due to inappropriate allocation of resources,” the authors wrote.

It also means medicine that could work for both sexes, could still have worse side effects for women.

In fact, of the 10 prescription drugs removed from market by the US Food and Drug Administration between 1997 and 2000 due to poor side effects, eight had greater health risks for women.

“Serious male biases in basic, preclinical, and clinical research were the main reason for the problem,” a 2018 study found.

“Scientists have often used only one sex (generally male) for experiments and applied the findings to both sexes, without solid grounds. These kinds of inadvertent extrapolations might cause unintentionally harmful results to the neglected sex and economic loss.”

And if women have a heart attack, their chances of survival are 23 per cent less than men’s when it comes to public resuscitation.

That, a 2017 study found, could be because people aren’t as comfortable resuscitating a woman they don’t know because it requires touching their chest.

“By uncovering this disparity, we’ll be able to think about new ways to train and educate the public on when, why and how to administer bystander CPR, in order to help save more lives – of both men and women,” lead researcher Audrey Blewer MPH said.

“Regardless of someone’s gender or how their body is shaped, delivering bystander CPR during cardiac arrest is absolutely critical, as it has been proven to double and even triple a victim’s chance of survival.”

Make your money work with Yahoo Finance’s daily newsletter. Sign up here and stay on top of the latest money, news and tech news.

Follow Yahoo Finance Australia on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance