How the world (and outer space) watches the Super Bowl

At 8:30 a.m. on Super Bowl Monday, 2018, with Tokyo’s notorious morning bustle in full flight, lifelong Philadelphia Eagles fan Dan Orlowitz dipped into Bar 894 Base in Nakano and settled in for the show.

At the same time, 1:30 p.m. Monday in Apia, Samoa, with NFL jerseys adorning walls around him, Cliff Bartley gazed up at a big screen and guzzled a beer. At 2:30 a.m. in Petrozavodsk, Russia, Stanislav Rynkevich did exactly the same.

Meanwhile, on Sunday evening, in towns in and around the Amazon Rainforest, Huan Almeida flipped to ESPN Brazil; George Bezerra fired up social media; Bezerra Silva kicked back with a soda and french fries; Ailzo Mendes Miranda preferred pizza; and Railson Vieira de Oliveira “scream[ed] with my mouth shut” to avoid waking up his family.

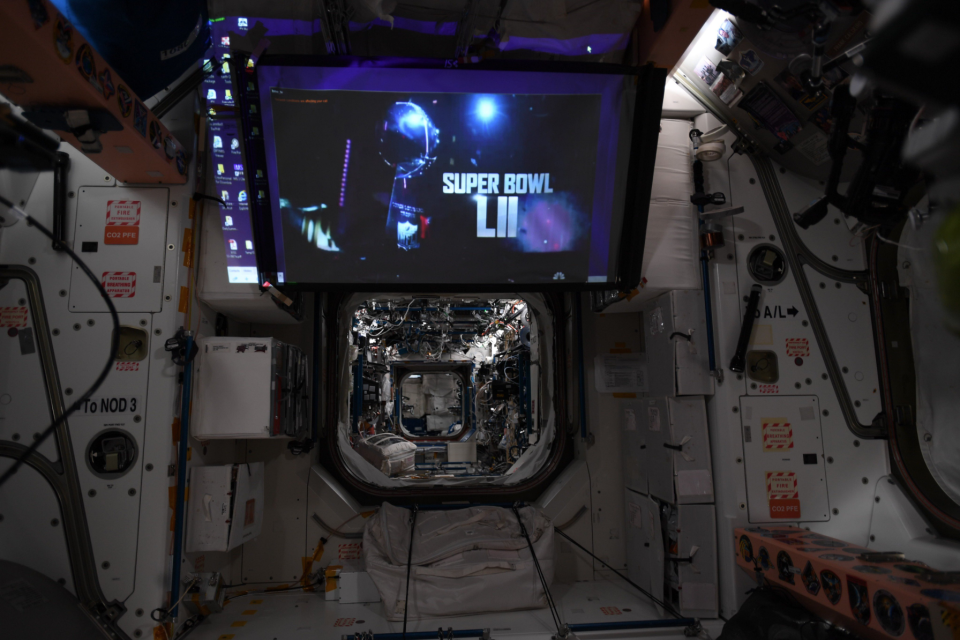

And as they did, Joe Acaba strapped himself to bungee cords in Node 1. He chowed down on hors d'oeuvres that had traveled 250 miles into Earth’s orbit. On the International Space Station’s main projector, well past his bedtime, while moving 17,500 miles per hour and circling the planet three times, he watched the most prolific NFL game ever, just like you and I did.

Because the Super Bowl, over half a century after its founding, is no longer simply America’s game. It’s something more. It isn’t the most-watched sporting event in the world. Nor does football boast anywhere near the global reach of soccer, basketball or cricket. But it has spread – slowly. Earth’s 7.8 billion humans are increasingly connected. Sunday’s showdown between the Chiefs and 49ers will be broadcast in around two dozen different languages, on all seven continents, in well over 100 countries. It’ll be watched on military bases and at Antarctic research stations and during flights. It’ll be widely available elsewhere via illegal streams.

And yes, it will even be accessible in outer space.

Yahoo Sports spoke with more than 20 people across the globe, including one fan at the South Pole, to get a sense of how the world watches the Super Bowl. What we found is that, although NFL fandom in many locales is a niche pursuit, the game is available almost anywhere.

Almost.

Super Bowl Monday?

Cliff Bartley was born and raised in Apia, the capital of tiny Samoa, a multi-island nation in the South Pacific that once lived a 364-day year so it could hop over the International Date Line. Back in the 1980s, it didn’t have a single TV channel.

But American Samoa, an adjacent island and U.S. territory, had a few. “So,” Bartley says, to watch the NFL, “we’d have to beam into American Samoa. It was black and white. The reception was pretty bad. You had to go and adjust your aerial outside to try and get a good signal from American Samoa.

“But if you loved football, you’d still watch it.”

And Bartley did. He latched onto John Elway and the Broncos. He started an unofficial NFL Samoa Club, a small group of local diehards who followed America’s most popular sports league from afar as best they could. Back then, most games were on Sunday mornings. Gradually, broadcasts became more plentiful and less fuzzy. For decades, on Super Sunday, the club would gather at a member’s house to celebrate the occasion.

Then, in 2011, Samoa flipped from east of the IDL to west. Super Bowl Sunday became Super Bowl Monday. Weekend became weekday. And the NFL Samoa Club … didn’t change a thing.

For the last three years it’s made arrangements at Taumeasina Island Resort. The members bring in projectors and American food. They decorate their space with NFL jerseys and flags. They hire a band for the afterparty. While many of their countrymen endure mundane Mondays at work, they arrive around 9 a.m., engross themselves in the game throughout the afternoon, then revel until midnight.

And they set a remarkably high standard for remote-locale Super Bowl festivities.

Elsewhere in the South Pacific, or the Caribbean, or on islands that might appear on lists of the 10 most remote places on Earth, NFL fan communities range from far less developed to non-existent. Most tiny-island tourism agencies did not respond to inquiries about Super Bowl-watching. A rep from Socotra, an Arabian Sea archipelago that belongs to Yemen, wrote back: “Must disappoint you. No one is interested in American football on Socotra.”

But on Earth’s least-populated recognized territory, the volcanic Pitcairn Islands, a British dependency home to 48 people, 3,400 miles off the coast of Chile, at least one person is interested. Her name is Melva Evans. She was born and raised there. She moved to Colorado, where she became a Broncos fan, but eventually found her way back home.

“I wish I could tell you that we watch [the] Super Bowl down here,” she told Yahoo Sports in an email. “Sadly, our broadband can be rather dodgy, at best; so, it's an effort in futility to even try. Also, up until almost a couple of years ago, internet costs would have been prohibitive to make the effort.

“We have a different internet provider now, and cost is no longer a factor; but, the connection is still dodgy. I'm giving it a Google search to find the best link up to give it a try, though. Wish me luck.”

Super Bowl around the globe

As Evans searches, some 11,000 miles away, the frantic streets of Mumbai, India, will overflow just like they would on any other Monday morning. Cars will screech. Pedestrians will weave between them. Mopeds and rickshaws will fight for their place. The Super Bowl will begin. It will be available on FanCode, an OTT streaming service. And the vast majority of India won’t care.

“I can’t even recall printing the outcome of the game [in the newspaper],” says Sukhwant Basra, a former sports editor at the Hindustan Times.

Adds Rohan Raj, a sports editor at the Times of India: “The public interest in this part of the world is almost nil.”

There are hundreds of millions of sports fans in the second-most populous country on Earth. Their fanaticism is reflected in whopping cricket viewership numbers – 345 million watched the Indian Premier League over a span of two weeks. But their complete disregard for the Super Bowl on the morning of Feb. 3 will be a reminder: While the U.S. stops in its tracks, the rest of the world, for the most part, either sleeps or keeps moving.

In Japan, where the game kicks off at 8:30 a.m. Monday, most city dwellers simply commute to work. They could stream the game on DAZN. They could stay home and watch on NHK, the nation’s main satellite channel. The NFL will also host viewing parties, including a few at Hooters. Some sports bars will open early and be “packed,” according to Orlowitz, the Tokyo-based Eagles fan. But mostly by expats – they, Orlowitz says, are “the only people who are really going to care.”

Hong Kong and Beijing boast similar scenes. “Many foreigners look forward to the occasion as a chance to enjoy a boozy day off work,” says Paul Ryding, a sports editor at the South China Morning Post. “Among locals,” however, “there isn’t a great deal of fuss.”

In Europe and Africa, the timing of the game is even more inconvenient. In England and Germany, where there are pockets of NFL fans, the game kicks off at 11:30 p.m. and 12:30 a.m., respectively. It finishes well after 3 or 4. In South Africa, it begins at 1:30 a.m. Johnny Chen, a Seattle native who lived in Johannesburg in 2014, remembers using a VPN to secure an American stream – and, most importantly, American commercials. He and his roommate invited friends and co-workers to their apartment around 10 p.m. for a braai – a South African barbecue. They then settled in for Seahawks-Broncos, stayed up past 5 enjoying the blowout, and arrived at work three hours later than normal. “The next morning was awful,” Chen says. But his boss understood.

In western Russia, kickoff is at 2:30 a.m. That doesn’t stop hundreds from gathering for a big Super Bowl bash in Moscow. And it certainly doesn’t stop Rynkevich and 15-20 fellow football fans from gathering at the dimly lit Green Street Irish Pub in Petrozavodsk. They make score predictions and paint faces. But the pub stops serving food and drinks at halftime. And by then, the rest of the northern lakeside town’s 270,000 people have long since dozed off.

The most robust Super Bowl culture outside North America might belong to Brazil, where the game begins at 7:30 or 8:30 on Sunday evening. A sizable community of football fans has developed throughout the country over the past decade. The most popular team is the Patriots. The most popular player is Gisele Bundchen’s husband.

“In Brazil,” says Felipe Von Zuben, who runs a Patriots fan club, “for the majority of the people, he is Gisele’s husband.”

For the Patriotas, Von Zuben’s club, the Super Bowl had become an annual event. Members from all 26 Brazilian states interacted online. They watched from their homes or friends’ homes or cousins’ homes or at bars. They felt connected to one another, and to something far grander; to millions of New Englanders 5,000 miles north of them whom they’d never met; to a region many had never visited.

Little did they know, they were also connected, by this same foreign sport, by this same unmissable event, to dozens of football fans 5,000-plus miles south of them – and even one above them.

Watching in outer space

Bill Coughran called me on what he described as a “clear and sunny” weekend morning, at 8:38 local time, with a 15 mile-per-hour wind whistling outside. It was, the Southern California native said, a “nice summer day.”

It was also 20 degrees below zero. Because Coughran was at the South Pole.

He spends American winters down there every year, facilitating research for the National Science Foundation. He’s also a football fan. In that sense, his job is slightly problematic. There’s no live TV at the pole. No NFL Sundays. There’s internet access, so there’s score-tracking, but no regular-season-watching.

There is, however, Super Bowl watching.

Every year, the game is shown at McMurdo Station, an American Antarctic research hub 850 miles north of the pole. It’s 2,400 miles directly south of New Zealand, meaning the Super Bowl occurs on Monday afternoon. And the work is too important to interrupt. “We still have to fly planes,” says Liz Kauffman, who “came out of the womb a Broncos fan,” and who’s been working austral summers in Antarctica for decades. “We still have to fly helicopters. We still have to issue gear. We have to cook meals.”

But when the busy schedule relents, they park themselves in a designated TV room for the game. An Armed Forces Network feed is transmitted to the station, then replayed on closed-circuit TV after hours. When Denver won the Super Bowl in 2016, Kauffman, her husband and a third Broncos fan sat in a superstitiously specific alignment, with pom poms, and “keys to the game” written on a whiteboard nearby. The broadcast quality is flawless. The only quirk: on AFN, there are no commercials.

A recording of the game then finds its way down to the Pole, via flash drive, on the next flight from McMurdo to Amundsen-Scott Station – usually several days later. Once Coughran receives it, he schedules the Super Bowl party. In the meantime, researchers who double as avid fans work hard to avoid the score. They then gather – 40 or 50 strong – to watch. Cooks prepare bar snacks, poppers and chicken wings. The scientists feast. “It’s an annual social event,” Coughran says.

It isn’t quite that in outer space. The International Space Station’s crew is a rotating cast that never includes more than three Americans. And the game begins at 11:30 p.m. But for astronaut Joe Acaba, in 2018, Patriots-Eagles was a must-watch. So he communicated with mission control, which arranged for a broadcast feed to be uplinked to a laptop. In Node 1, one of the space station’s smaller modules, he set up a projector and snacks. And to avoid floating, he hooked himself to bungee cords running along the floor. “It’s almost like you’re in a lounge chair,” Acaba says. “It’s super comfortable. It’s pretty cool.”

Remarkably, the feed was as live as can be, “not any different than the TV broadcast in your house,” a NASA rep told Yahoo Sports. The only issue is satellite interruptions. Sometimes they last 10 seconds, sometimes longer – “10, 20, 30 minutes, even up to an hour,” Acaba says. The game goes dark. It resumes with the astronaut completely unaware of what he or she missed. “It just adds a little bit of extra drama to the game,” Acaba jokes.

In a way, for him and Coughran, and for thousands of expats around the world, foreign Super Bowl watching isn’t the same as a Sunday evening gathering with friends and family. The camaraderie, in some cases, is absent.

But as they watch, they know that more than 100 million countrymen are as well. That understanding, for at times lonely world travelers, is special.

“Being able to watch a sport, like the Super Bowl, World Series – [or] your favorite TV show, or talking to the family – it’s really important when people are on expeditions,” Acaba says. “Having that connection to home is really important. I love football. But the bigger part is, you’ve got millions of people that are watching this thing. And you’re still making that connection even though you’re 200 miles above the Earth. We work hard up there. But we’re humans, and we like to keep that contact with what folks are doing on Earth. That’s what makes it fun.”

More from Yahoo Sports:

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance