Hokusai: The Great Picture Book of Everything at the British Museum review

The best known Japanese artwork for us in the West is probably (Katsushika) Hokusai’s colour woodblock print, The Wave, which appears across every medium known to man, from tote bags to mouse pads. In fact, Hokusai’s output was enormous over the course of his long life (1760-1849) and the British Museum is now exhibiting an exciting new purchase – last year – of 103 never-exhibited Hokusai brush drawings, intended for an apparently unrealised project called The Great Book of Everything. The drawings surfaced in 1948 then disappeared off the radar until the sale in Paris in 2020, two centuries or so after they were made. They’re small, just over picture postcard size, in black and white ink, fitting neatly into a little parcel which was in turn tucked away into a wooden box.

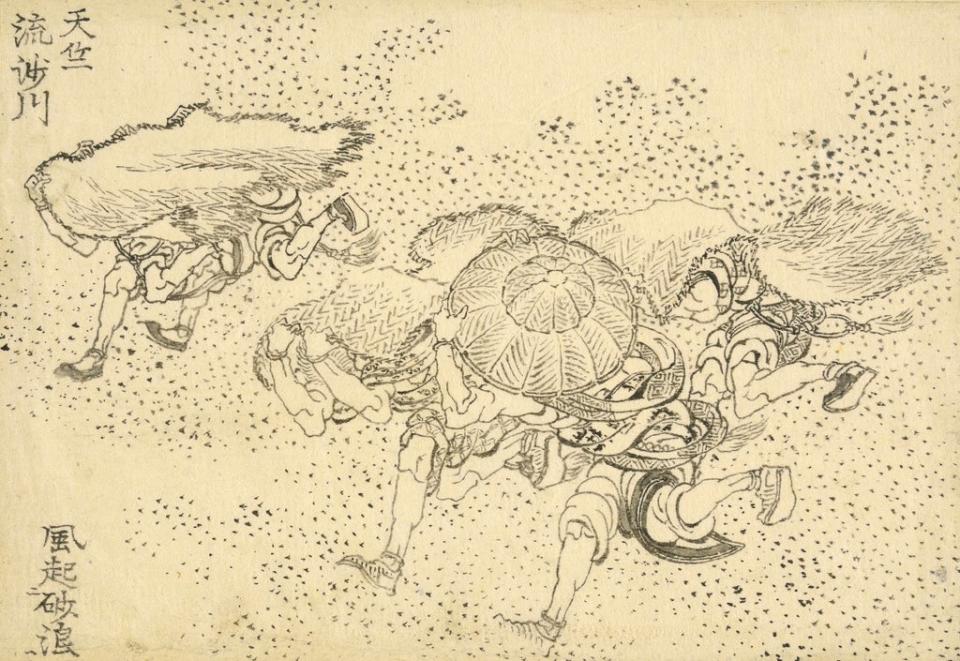

Being small and monochrome, these drawings don’t pack an immediate visual punch; you can see the detail better in the excellent catalogue edited by Timothy Clark which replicates them all. The Great Book of Everything may have been intended as a cross between a young person’s illustrated thesaurus and an encyclopedia, with the “everything” encompassing the origins of the world, scenes from India and China, the activities of Buddhist deities and their disciples, the adventures of heroes, and assorted animals and birds. There are elements here of Sir John Mandeville’s Travels (people from the land of the long-eared and the flying-head barbarian), Heath Robinson (I’m thinking of the lugubrious elephant), a medieval bestiary and comic strips.

The curators use the term manga in our sense more than once and you can see why. There’s one image here of a baddie getting killed by a lightning strike and the light rays might just as well have the caption “Kerpow!”; this is manga a century before manga happened. It’s also a view of the world at the end of the two centuries in which Japan existed in its own lockdown, with access to the wider world restricted to international trade via the port of Nagasaki. Nonetheless, Hokusai ventures into the imaginative world of China and India and their gods and creatures with engaging confidence, though the charming camel drawings were, it seems, based on actual beasts that made it to Japan.

These are masterly little pieces, some busy, all vivacious, some humorous and many quite beautiful. A bear in a waterfall and cats in an hibiscus bush are marvellous; so too is a hero ascending to the heavens to capture the moon – it’s much smaller than on the poster of the museum. Oh, and you get to see a couple of versions of The Wave too.

British Museum, to January 30, britishmuseum.org

Read More

Jimi Famurewa reviews Supa Ya Ramen: Raucous, delicious — and vital

Queen declines Oldie award as she says ‘you are only as old as you feel’

THG founder Moulding gives up golden share in governance overhaul

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance