Updated: The deadline for My Health Record has been extended — here’s what you need to know

Update: Wednesday 14 November 2018

The deadline for opting out of the government’s My Health Record scheme has been extended to 31 January 2018.

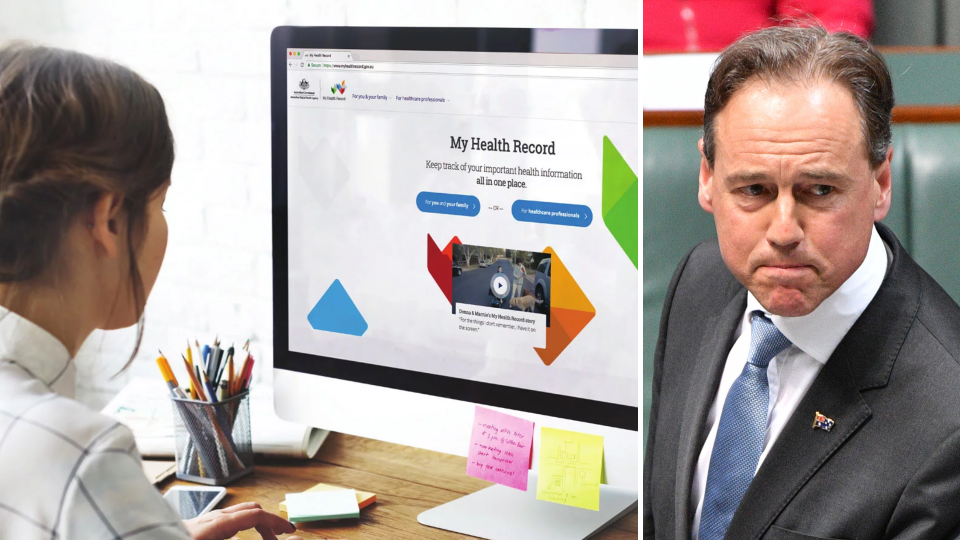

Off the back of mounting concerns about the scheme’s privacy and security risks, Health Minister Greg Hunt announced on Twitter at 2:22pm that the deadline had been extended by three months following negotiations with the Senate crossbench.

Today the Government worked with the Senate crossbench to extend the opt-out period for #MyHealthRecord.

The opt-out period will be extended until January 31, 2019, however, it’s important to note that people can opt-out at any time.

— Greg Hunt (@GregHuntMP) November 14, 2018

Prior to the deadline extension, the opt-out date would have been tomorrow (Thursday 15 November 2018).

Earlier on Wednesday, Labor attempted to extend the deadline by 12 months, a motion that was voted down by the Senate, which has now agreed to the three-month extension.

Many Australians attempting to opt out of the scheme today turned to Twitter in frustration to vent about server failures on the My Health Record website.

#MyHealthRecord opt-out going as expected. pic.twitter.com/9oSsPxENd1

— Caleb Wise (@calebwise) November 13, 2018

At the eleventh hour, when those poor Aussies who have only just realised they should opt-out are trying to do that, the #MyHealthRecord portal is borked 🌵

If they can’t handle heavy website traffic how are they going to handle 18 *million* sensitive files? pic.twitter.com/85ZNZvOw9z

— Dr Belinda Barnet (@manjusrii) November 14, 2018

MHR is as an online summary of your health information held by the government – the idea being that Australians will be able to store all their health information in the one place, so GPs, pharmacists, physios, dentists and insurers can easily access your records no matter which clinic or hospital you go to.

Also read: The ANZ Bank has tough new rules for home loans

But if you don’t opt out by the deadline, a MHR profile will automatically be created for you.

Concerns have been raised by medical practitioners, industry experts, academics, citizens and law firms alike about the rushed roll-out, arguing the project risks privacy and data security.

So why have over a million Aussies already opted out?

MHR data is sketchy

Rural doctor and Flinders University Rural Clinical School of Medicine senior lecturer Tim Leeuwenburg described MHR as a “shambles” in an article for Medical Republic.

“One of the biggest problems we face in healthcare is the disconnect between various systems,” he wrote. “The failure of different parts of the health system to communicate and perform a proper handover of care is a major safety risk.”

Doctors and medical practitioners would love to have a centralised health record that can hold patients’ data in one place, regardless of location, he noted. As it stands currently, your medical file is held by your clinic only, meaning doctors of another clinic can’t see your file.

However, MHR is not the solution to this problem. “Instead of a nuanced system that integrates into the clinical workflow, the MHR has been likened to a ‘shoe box’ of files,” the rural doctor wrote.

“Navigation is difficult as the user is faced with a smorgasbord of PDF documents which can be slow to load… and hard to collate and assimilate. This is likely to get worse as more information is added, unless the content is aggressively curated.”

Your privacy and data security isn’t well-protected, putting you at risk

In an article published in The Conversation, the University of New South Wales’ Katharine Kemp and David Vaile and the University of Canberra’s Bruce Arnold pointed to the project’s security risks as one of three core reasons why Australians ought to opt out.

“Health records are valuable as a means of identity theft due to the wealth of personal information they contain,” the academics argued. “They are a huge prize for hackers, fetching a high price on the Dark Web.”

Also read: Terrorists could be using Aussie charities to launder cash

Furthermore, any medical professional with access to the right software can see your records. Leeuwenburg notes that MHR tracks which organisation has opened the file, but not which individual.

“So if Hospital X opens your file, you really don’t know if it’s uber-specialist Prof X who is perusing your file… or a bored pharmacist, an idle radiographer or the admin clerk. They will all have access.”

If that isn’t enough, UNSW and UOC academics point out that the government has a bad record for protecting the security of its citizen’s health information.

Your permission or consent to share this information with third parties is also not being expressly asked for, as it ought to be by law.

“Unfortunately, and predictably, health apps are already securing ‘consent’ through obscure, standard form contracts so you might not be aware the app owner could sell your sensitive medical information to others.”

Vulnerable Australians could be in danger

Graham Doessel, CEO of credit reporting law firm MyCRA Lawyers, told Yahoo Finance that MHR can potentially place multiple Australian groups and communities at risk, including younger Australians and those at risk of domestic violence.

MHR leaves “potential for abusive spouses to track children of relationships via My Health Record access (e.g. which clinics they are visiting)”, Doessel said.

“Teens looking into sexual health via [their] GP may unknowingly have this data uploaded also. [It] may discourage youth consultation.”

Additionally, rural health workers have flagged that not enough oversight and effort has been given to explaining MHR to non-English speaking Aboriginal communities with minimal internet access or digital or financial literacy, as reported by the ABC.

Needing to opt out ‘flies in the face’ of best practice

The fact that you need to go out of your way to opt out at all is bad practice.

“The opt-out consent mechanism for MHR flies in the face of global best practice for informed consent – and our own federal privacy regulator’s guidelines on the sort of consent necessary for use of health information,” the academics argue in the article.

Also read: Solving the biggest problem with traditional financial advice

“Consent for use of personal information should be expressed, fully informed, easy to understand, and should require action on the part of the individual.”

“MHR disregards all of those principles.”

The ‘safeguards’ aren’t that safe

The details you need in order to gain access to someone’s MHR is their first initial, surname, gender, date of birth, and the first nine digits of their Medicare card.

But there is a way that healthcare professionals can do a reverse lookup of your Medicare number anyway, leaving Australians relatively vulnerable to identity theft, fraud, or blackmail.

For instance, someone with ill intentions with access to your MHR could blackmail you if your record has information about a previous STD, an abortion, or health information that could count against you in a business deal, Doessel told Yahoo Finance.

How could someone find my details?

It’s easier than you think, and doesn’t involve much more than a solid snoop session on Facebook. Doessel points out that, just by looking at someone’s Facebook profile, you can glean enough information to constitute three ID points from basic details such as their name and birthday.

Also read: Small business owners beware: your access to credit is under threat

If you scroll enough through their photos or posts of birthdays, social events or reunions, there may be mention of other crucial details that could represent an extra data point identification.

With all that information, there’s nothing stopping you from requesting a replacement Medicare card.

How do I opt out?

The last day to opt out has now been extended to 31 January 2019. To opt out, there are three ways:

Online: follow the instructions at optout.myhealthrecord.gov.au to opt out. You can follow this link here. You will need your Medicare card or your driver’s license handy in order to verify your identity.

Over the phone: Ring 1800 723 471.

Through the mail: You’ll have to fill out a form and send it by snail-mail. 2385 rural and remote Australia Post offices will soon make these forms available through 146 Aboriginal community health organisations as well as 136 prisons.

Make your money work with Yahoo Finance’s daily newsletter. Sign up here and stay on top of the latest money, news and tech news.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance