As new era of NFL players face social injustice, filmmaker reflects on the fight to integrate the league

George Preston Marshall, the founding owner of Washington’s NFL team, has been in the news of late, which brings back memories for Theresa Moore.

A few years ago, Moore, a filmmaker and documentarian, produced “Third and Long,” about the Black men who integrated the NFL and their struggle for respect within the league and outside of it during the struggle for civil rights.

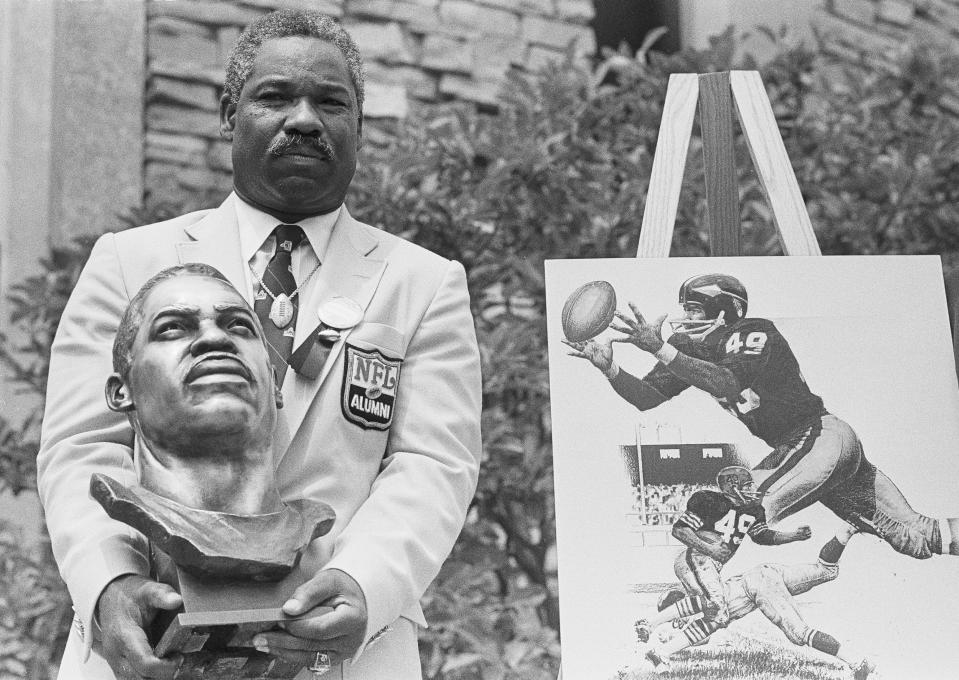

One of the stories she heard was from Gwen Mitchell, the wife of Pro Football Hall of Famer Bobby Mitchell. In 1962, Mitchell was the first Black player to play for Washington. The Cleveland Browns traded him there when Syracuse running back Ernie Davis refused to play for Marshall, who integrated the team only when the federal government stepped in.

“So [Mitchell] is out to dinner with his wife and another couple, and Mr. Mitchell swore it was a senator or some other politician, but they walked by and spit on him as he’s at dinner with his wife,” Moore said this week. “And so [Mitchell] starts to get up and whoever it was that was with him put a hand on his forearm or shoulder and just said, ‘You know what, you’ve got to sit down, because if you do this, there will never be another Black player here for years.’

“So Mrs. Mitchell talks about having to watch her husband’s reaction in that moment, and what she’s feeling for him as a Black man and his dignity and all that versus what’s the long game,” and doing his best to make sure he wasn’t the first and only African American player on the team.

On Wednesday, there were reports that Washington will remove Marshall’s name from the team’s ring of honor and history wall, which came a few days after crews removed the memorial to Marshall outside of RFK Stadium.

The edits don’t erase the public way Marshall fought to integrate his team, his staunch segregationist beliefs or any pain he caused the Black players on Washington’s roster during his time as team owner. History will preserve his behavior and words.

Like in “Third and Long.”

“We spent a good part of the film talking about him,” Moore said. “On one side, he was a great showman and is the reason we have halftime shows and all this stuff. But on the other side is this staunch segregationist — people forget at the time the Redskins were the southernmost team [in the NFL], so he had the flags and playing ‘Dixie’ and had a television station so his market was the South, and he wasn’t trying to disrupt it.”

The federal government paid for the construction of RFK Stadium in Washington, and Marshall had a 30-year lease to use the facility. One year into the lease, Attorney General Robert Kennedy and Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall pressured Marshall to integrate the team or the lease would be torn up.

The letter Udall sent to Marshall and Marshall’s response are shown in “Third and Long.”

“Marshall pretty much writes back, ‘Go pound sand.’ He was not going to have any of it, but then he realizes that he was not going to win this battle,” Moore said.

Were it not for Marshall, Washington’s team could have been quite different. In the movie, Mitchell has conversations with Jim Brown, when they believed it must be great to play in Washington because of the higher population of African Americans in the city.

But once Mitchell was traded to Washington and other Black players followed, they realized it wasn’t as great as they’d hoped.

“Deacon Jones was one of my favorite interviews on the whole project. He ended up playing on the Redskins, and he talks about how every day before he would go play the game, he’d spit on the statue of George Preston Marshall and keep walking,” Moore said.

Jones spent his final NFL season in 1974 with Washington. Marshall died in 1969, but his legacy was well known.

The stories of Mitchell and Jones aren’t the only ones in “Third and Long.”

Walter Beach, who played for the Boston Patriots and Browns during a six-year career that began in 1960, recalled when he was reading “Letter to the Blackman in America” by Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad on the team plane. Browns owner Art Modell told Beach he couldn’t read the book. Beach, supported by Brown, told Modell that he could tell him what to do as a player, but he would not tell him what to do as a man.

Or Henry Ford, whose NFL career was just two seasons. Why? When Ford was with the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1956, someone was listening in to a phone conversation he was having and reported back to the team that Ford was dating a young white woman.

“Henry Ford has this amazing game and is called by the front office and they say, ‘You can’t do that. You can’t date this young white woman,’ ” Moore said. “Mr. Ford said, ‘I’m not dating her, that’s my wife.’ ”

The Steelers told Ford he had to choose between his wife, Rochelle, and the team, and Ford, of course, chose his wife. He was cut by Pittsburgh, where he’d started all 12 games for that season, and never played again.

Brown and others were part of the civil rights movement, just as NFL players now are part of the new movement. Moore agreed that as much as some things have changed, some things haven’t changed for Black players in the league.

“We’ve tried to communicate with the league to suggest that they show the film again because it’s still relevant,” she said. “Many of these athletes were social justice advocates and fighting for things — players were going down and signing people up for voters’ rights, Jim Brown created the Negro Industrial and Economic Union, which was intended to raise capital for Black businesses. These athletes were still very much active and pushing for social justice and civil rights issues.

“So it’s no different than what Colin Kaepernick is trying to do. It’s not like all of a sudden athletes have become these big activists. These guys were doing it and for much less money on the football side of it. It’s very interesting for people to act like there wasn’t the [activism], whether the football players or the John Carloses and Tommie Smiths of the world — you had lots of people who were activists and so to ask people not to use their platform or in the case of LeBron [James], ‘shut up and dribble,’ that doesn’t make sense because athletes have been doing this for a long time.”

More from Yahoo Sports:

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance