America’s health system is still in crisis after its biggest cyberattack ever—but the ‘catastrophe’ is just a blip for the giant company that got hacked

In early March, Joe Martin, the owner of Function Better, a physical therapy clinic in Yorkville, N.Y., looked at his business bank account and thought he’d been hacked. After more than 22 years in operation, Martin, an orthopedic clinical specialist, had a good sense of the revenue that came in the door each week, and so he was alarmed when his statement showed the account had been severely depleted.

Martin hadn’t been hacked, but Change Healthcare—the clearinghouse that touches from one-third to one-half of all medical claims in America, including those submitted by Function Better’s billing firm—had been. Change processes a stunning $1.5 trillion in claims annually in the U.S. And the February ransomware attack on the subsidiary of United Healthcare, which has been described as “the most significant and consequential cyberattack on the U.S health care system in American history,” has affected almost every corner of the industry.

Seventy-four percent of hospitals reported in March direct impacts to patient care as a result of the cyberattack, and 94% said they felt financial impacts. And the hack is still snarling the health care system: As of April 3, 36% of physician practices reported a suspension in claims payments, while 32% said they were unable to submit claims for payment, a survey by the American Medical Association found. “For most physicians, functionalities dependent upon Change Healthcare systems are still not up and running, at least not completely,” the AMA told Congress last week.

Martin’s practice is among them. Since the cyberattack forced Change offline on Feb. 21, Function Better has been reimbursed for just a tiny fraction of the services it has provided. And those payments haven’t come through Change, but through the heroic efforts of Martin’s billing company, which has started typing claims line by line—"like in the 80s,” he says—into insurance portals. But, right now, Martin celebrates that progress. When we first spoke in mid-March, Function Better hadn’t been paid at all. “We are losing $25,000 a week in cash flow,” Martin told me, four weeks and $100,000 into the ordeal. Until the crisis, Martin had no idea his billing company even used Change’s technology, let alone that his practice’s fate and that of his 14 employees depended on it.

Martin had gone so far as to hire a bankruptcy attorney, though when we spoke, he had developed a workaround to muddle through the cash crunch: It involved his other business, a physical therapy practice based in Florida that accepts only Medicare and private pay (and thus doesn’t solely depend on insurance claims being paid). “There’s times in the last four weeks that I carried bags of cash on [the] airplane to make sure my employees were paid,” Martin said.

Multiply Martin's dilemma by thousands of providers—from Fortune 500 hospital chains to single-office independent physicians—and the size and seriousness of this breach becomes increasingly clear. And after weeks of staying mum, UHG and Change Healthcare are beginning to acknowledge just how serious the problem is.

Late Monday afternoon, UHG shared the stunning, preliminary findings from its investigation: “Based on initial targeted data sampling to date, the company has found files containing protected health information (PHI) or personally identifiable information (PII), which could cover a substantial proportion of people in America.” Put more directly: A substantial proportion of people in America—likely tens of millions if not hundreds of millions, given the scope of Change's operations—had their data breached in this cyberattack. (UHG also admitted publicly for the first time that it had paid a ransom to the hackers yesterday.)

Noting it would likely take several months before UHG could identify and notify impacted individuals, the company promised to “immediately provide support and robust protections,” pointing people to a dedicated website and call center that will provide free credit monitoring and theft protections for two years. UHG's own losses due to the cyberattack are expected to total up to $1.6 billion this year, a mere blip for a company that brought in $372 billion in revenue in 2023. But individual practitioners and their patients face far greater risks, and they're being left to wonder how much worse things will get before they get better.

A ‘catastrophe’ that has flown under the radar

Many see the February cyberattack as a cautionary tale about America’s highly fragmented but fast-consolidating health care ecosystem. It’s one that points to the vulnerabilities of a landscape shaped by forces—health care economics, and regulatory and technological change—that have made it harder and harder for small and independent providers to compete.

And the results are not just financial perils for providers: When health workers lose access to their electronic systems and time-sensitive patient data in such attacks—as they more and more frequently do (141 hospitals were hit last year)—it can pose serious safety issues and even cost lives.

The hack, which a Russian ransomware cybergang known as ALPHV/Blackcat claimed credit for, has flown somewhat under the radar, despite some national media coverage. But amid the ongoing fallout, confusion, and disruption for health care providers across the country, there’s a sense among those experiencing it that the extent of the crisis isn’t being covered. For those in smaller practices like Martin’s, the whole thing has been, in his words, a “catastrophe.”

Industry giants have been affected too: HCA Healthcare, the nation’s largest for-profit hospital chain—No. 66 on the Fortune 500 last year—relied on Change and experienced “temporary cash flow” impacts, though it managed to switch clearinghouses roughly 10 days after the attack. CVS Health, America’s sixth-largest company and UnitedHealth’s chief competitor, nonetheless runs a quarter of its insurance claims through Change. Large insurers such as Cigna and Elevance acknowledged their flow of claims were significantly impacted too. The U.S. military’s pharmacies depend on Change, and many transactions involving the federal government, the nation’s largest purchaser of health care, pass through it as well. And since 2013, Change has been the platform for CommonWell Health Alliance, which facilitates the exchange of 250 million patient medical records every month (for example, to allow your doctor in California to access X-rays you had taken in Texas). In other words, it would be hard to be a patient, provider, or payer in today’s health care ecosystem and not be exposed to Change technology in some way.

“The actual commerce of the health industry just stopped, and no one seemed to care,” says Boe Hartman, cofounder and chief technology officer for Nomi Health, a health care payments company, that saw its own flow of claims and payments freeze as a knock-on effect from the cyberattack. Hartman, a former Goldman Sachs partner, spent most of his career in the banking industry, and he’s been stunned, given the size and import of health care industry, that the fallout from the cyberattack hasn’t generated the same wall-to-wall coverage as last year’s Silicon Valley Bank collapse.

Catherine Reinheimer, the practice manager of Foot & Ankle Specialty Center in Willow Grove, Pa., agreed. “It’s just not being covered by the media,” she says. She recalls it coming up only briefly on the NBC Nightly News: “I heard Lester Holt say one sentence.”

Six weeks after the attack, her practice still hadn’t received payments or clear guidance on the situation. She had found her congressperson, whom she has begun speaking to on a regular basis, a more accessible source of information than the company.

Even now, two months out from the attack, many of Change Healthcare’s services have yet to be fully restored and some of the most burning questions remain unanswered: How did this happen, and who’s behind it? What—and how much—personal health data has been compromised? And most urgently for Martin and his peers, can the smaller health care providers still struggling to get paid survive this mess? There are still no reliable and comprehensive numbers on the scale of disruption, given the myriad ways payers, providers, and other entities are connected to Change and the varying degrees to which they were dependent on it. One thing is very clear: This catastrophe is not yet over.

New, urgent questions continue to crop up. Has a second ransomware group—as reported by trade publications and other outlets recently—gained possession of Change’s stolen data, started leaking it online and demanding ransom from Change customers? To that question, and others related to the ransomware attack, UnitedHealth Group says in a statement to Fortune: “This attack was conducted by malicious threat actors, and we continue to work with the law enforcement and multiple leading cyber security firms during our investigation.” UHG did acknowledge in a statement provided to Fortune that “A ransom was paid as part of the company’s commitment to do all it could to protect patient data from disclosure.” (UHG had been silent until yesterday on that matter, despite reporting by Wired weeks ago that suggested the company had made a $22 million ransom payment to the suspected perpetrators.)

'Every man for himself'

The critical and vast role that Change, a little-known health technology business, plays within America’s sprawling $4.5 trillion health system has been a revelation to nearly everyone in the sector in the ongoing fallout from the February cyberattack. Acquired for $13 billion by UnitedHealth Group in a deal that was completed in 2022, Change is buried, like the tiniest nesting doll, inside the $372 billion juggernaut’s $227 billion health services arm, Optum, and integrated into its $32 billion data analytics unit, Optum Insight. In other words, Change is a subsidiary of a subsidiary of a subsidiary.

So it shocked many to see that when UnitedHealth powered down Change’s systems, its absence unleashed unprecedented and utter chaos upon health care entities everywhere: halting pharmacy transactions, crippling computer systems, and upending administrative processes and payments. The situation has left affected providers feeling powerless as they contend with convoluted and labor-intensive workarounds (think phone, fax, and mailing paper claims), perilous financial decisions, and little clear information about what to do and what to expect.

“Operationally, it’s a nightmare,” Martin said. “A lot of unknowns come with not having that kind of cash flow.”

While not everyone is resorting to carrying bags of cash across the country, he’s hardly the only health care business owner to turn to extreme measures: The president of Martin’s billing company obtained a multimillion-dollar line of credit to help get his decades-old firm through the crisis, he said in a video on his company’s website. Fran York, a nurse practitioner and the owner of Bear Pond Family Medicine & Pediatrics in Enfield, Conn., tapped into her retirement account and closed her practice for a day and a half so her staff could focus on stuffing envelopes to mail paper claims and other billing workarounds. The AMA’s April survey found that 55% of respondents had used personal funds to cover practice expenses in the aftermath of the cyberattack. And even so, 44% of practices reported that they were unable to purchase supplies, and 31% were unable to make payroll.

“It’s every man for himself,” said Reinheimer, the Foot & Ankle Specialty Center practice manager who, when we spoke in late March, described the situation as dire. She had recently mailed a letter to the practice’s vendors notifying them that the center would be unable to fulfill its financial obligations for the foreseeable future due to the cyberattack on its vendor’s vendor. “We’re hemorrhaging money. And that’s crazy. We shouldn’t be in this position.”

Few would disagree with that sentiment. In the wake of the hack, many now put Change in the same category as the recently collapsed Francis Scott Key Bridge: underappreciated and inadequately protected critical infrastructure.

“I think most physicians had no idea that Change Healthcare touches more than a third of all health care transactions in the nation,” says Dr. Jesse Ehrenfeld, the president of the American Medical Association (AMA) and an anesthesiologist, who adds the episode has been eye-opening when it comes to how “a single dominant player is driving so much of what's happening.”

To Benjamin Jolley, a pharmacist who works with the American Economic Liberties Project, a nonprofit focused on antitrust advocacy, the hack is the predictable result of consolidation run amok and proof that after years of wide-ranging M&A, UnitedHealth Group has gotten too big. “All roads lead to United,” he says, “and that to me feels like a very large systemic risk.”

Rep. Anna Eshoo, a Democrat from California, went a step further at the House Committee on Energy and Commerce meeting last week: “The attack shows how UnitedHealth’s anticompetitive practices pose a national security risk.”

A health care behemoth

When UnitedHealth announced its plan to buy Change in January 2021, executives framed the deal as an almost magical fix. The vision was to “reduce friction” in America’s highly inefficient and bewilderingly complex health care system—speeding payments, simplifying process, and ridding the system of administrative waste. The streamlining power of the new Optum-Change entity, a corporate press release promised, would mean better outcomes, lower costs, and improved experiences for everyone.

That’s a claim that has been made repeatedly to justify big health care companies getting bigger in recent years. And they’ve gotten very big. A year ago Fortune looked at a trend that had become too glaring to ignore: Health care companies are swallowing up the Fortune 500. Last year, the industry accounted for eight of the nation’s 25 largest companies, compared to zero in 1995.

A couple of decades ago, UnitedHealth was primarily just a health insurer and CVS a retail pharmacy chain. In the time since, those companies (and others like them) have transformed themselves, through several rounds of massive M&A, into all-purpose, health-system-spanning giants. They’re now insurers and pharmacy benefit managers and primary care clinics and home health companies. They argue that these new vertically integrated corporations are the answer to America’s expensive and hard to navigate health system. By bringing all these assets together, they say, they can better align payers and providers—long-standing antagonists—and leverage all their data to drive higher-value, better coordinated care. Of course, many are skeptical of these claims and the notion that these highly profitable incumbents should be trusted with such broad power over America’s health system.

For better or worse, Change represents a lot of that power. As the nation’s leading claims clearinghouse, it has often been described as the “pipes” of the health care industry, routing information and payments between payers and providers in a staggering 15 billion transactions per year.

The pipes analogy actually understates Change’s scope and complexity. The company’s platform offers close to 200 distinct technology services, many of which run through a provider’s electronic health record system and automate all sorts of back-end processes—scheduling appointments, checking eligibility and prior authorizations, offering imaging software and clinical decision support tools (i.e. instructing providers on what tests or procedures to run), facilitating the exchange of prescriptions and laboratory tests, and so on.

For insurers, Change provides tools that steer patients toward low-cost providers and quickly adjudicate claims. Even before Change was acquired, those tools supported most of the industry: 2,200 government and commercial payer connections, 900,000 physicians, 118,000 dentists, 33,000 pharmacies, 5,500 hospitals, and 600 laboratories. It’s unclear where those numbers stand now that Change’s business has been subsumed by Optum Insight, but surely, it’s still a lot. Optum Insight now facilitates 23 billion transactions annually and touches “285 million lives of clinical and claims data” according to 2023 UnitedHealth investor conference materials. (That’s more than 85% of the U.S. population.)

Not everyone thought the merger of these wide-reaching, many-tentacled entities was a healthy development for American health care, though a system-crippling cyberattack was not the scenario that government lawyers warned of when they tried to block UnitedHealth Group’s acquisition of Change in 2022. Their concern was about “giving United control of a critical data highway.”

The DOJ’s antitrust attorneys argued that in acquiring Change, UnitedHealth Group would be gaining an outsize claims processing market share as well as access to vast troves of its competitors’ proprietary data that it could use to its advantage to edge out health insurer rivals. A federal judge, persuaded by UHG’s arguments that it was in the company’s best interest to maintain a strict firewall between its insurance business (UnitedHealthcare) and its health services arm (Optum), allowed the merger to go ahead in 2022 after United sold off its claims editing business.

What role UHG’s ownership of Change played in the current crisis is a matter of vastly different opinions. “UnitedHealth was a target because of its size,” Eshoo asserted at the House Committee on Energy and Commerce hearing last week. Others point to cybersecurity vulnerabilities that tend to arise with M&A and in the messy process of integrating different technology systems and teams and ask why UHG appears to have been so ill-prepared and poorly defended for such an attack.

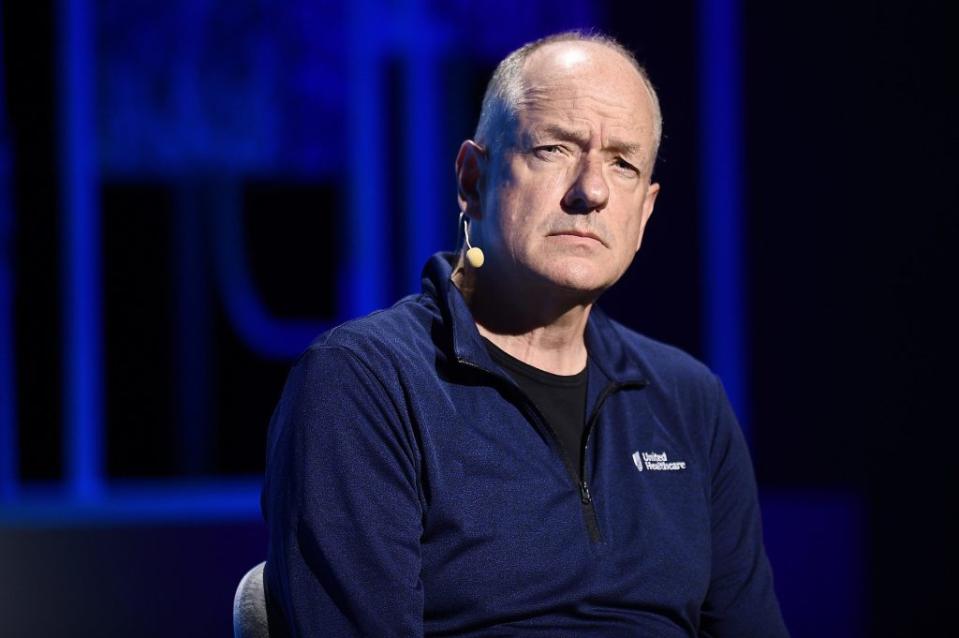

UHG CEO Andrew Witty, meanwhile, speaking on a company earnings call on April 16, suggested his company’s bigness had saved the day. “Cyberattackers unfortunately created another true validation of why [acquiring Change] was the right thing to do,” he said. “We were able to bring to bear the substantial resources of UnitedHealth Group…resources which a stand-alone Change Healthcare would not have had access to on its own.”

Confusion reigns

When companies lost access to Change’s services after the cyberattack, few had readily available alternatives. Nor, in the beginning, did they think they’d need them. Like Foot & Ankle’s Reinheimer, many assumed—and were not told otherwise—that what they were experiencing was a mere glitch, the sort that happens from time to time and usually gets resolved in minutes, or a couple of hours. For the first eight days of the cyberattack, updates on Optum’s support page included the vague and misleadingly reassuring note: “The disruption is expected to last at least through the day."

Switching clearinghouses isn’t a simple fix: It can be a monthslong process, so many health care businesses waited, assuming a company as well-resourced as UnitedHealth Group would have service restored soon. And indeed the issues at most pharmacies, where the impact of the hack was particularly immediate, urgent, and visible—patients couldn’t get their medications in many cases—had been resolved within the first week.

Many of Change’s largest clients were kept in the dark or offered vague bromides to placate them while their systems were down. The “repetitive talking point for weeks was, ‘We're currently down due to a cyber incident, and we're working on it,’” says Paul Wilder, the executive director of CommonWell, the network for sharing hundreds of millions of medical records each week. His understanding of the situation changed when, a few weeks into the crisis, Change started recommending its customers turn to competitors to get their claims moving. “When Ford says ‘go buy a Chevy,’” he says, “that’s when you know things are not great.” (CommonWell saw its service restored three weeks after the cyberattack.)

As the days and weeks passed without payments for claims, providers scrambled to find workarounds and access loans that the federal government and Optum offered certain providers. But accessing those funds took time and manpower that many small providers didn’t possess. Word quickly spread that Optum’s advance-payment program was so stingy—offering $100 or $200 per practice in some cases—and the terms so onerous that it wasn’t worth the bother. (At the government’s urging, Optum significantly upped those payments; as of April 22, it had advanced over $6 billion in payments to providers.)

The AMA’s Ehrenfeld says that while UnitedHealth has been far from perfect in responding to the cyberattack, he credits the company for at least “being engaged.” He and others are more critical of the other large commercial insurers that were reluctant to take similar steps—advancing payments or waiving prior authorizations—that would have eased the situation for providers.

That these companies continued collecting premiums from customers (and interest on that money sitting in their coffers) while health care providers struggled with cash flow has been especially infuriating to some.

"The average physician practice has only a few weeks to a month worth of cash on hand in their practice,” Dr. Adam Bruggeman, an orthopedic spine surgeon from San Antonio, told the House Committee on Energy and Commerce last Tuesday. “Insurers like United Health Group have plenty of data to understand the usual charges from and payments to a practice in a typical week. There's little to no reason why insurers could not have continued to make weekly payments based on the physician’s unique history and then reconciled once the clearinghouse outage was resolved. Recall that insurers are paid premiums in advance of care and have the money on hand.” (AHIP, the national organization representing health insurers, disputes the characterization.)

Unanswered questions

Since mid-March, government officials and industry leaders have said that the health care system is in the “last mile” of this crisis, but for many weeks updates from UnitedHealth—initially tracked on its “Impacted Applications Status Dashboard”—have indicated otherwise. As of April 23, only nine of 27 functions were listed as “service fully restored.”

UHG's Monday press release offers an updated picture, suggesting that America’s health care system has bounced back from the disruptive hack. The release claims that pharmacy services are functioning at 99%, Change’s payment processing at 86%, and medical claims across the U.S. "now flowing at near-normal levels” (albeit due in part to “other methods of submission”). UnitedHealth would have more visibility on these issues than most, of course. But most people Fortune spoke with didn’t see their reality reflected in the company’s rosy spin. “The industry is still dealing with [the impacts of the cyberattack],” says Boe Hartman. “I’m having a challenging time reconciling these two stories."

As bad as it has been, it could have been worse, experts say. Change and Optum had not yet completed the integration of their systems: They remained essentially separate environments at the time of the attack, apparently sparing UnitedHealthcare, the nation’s largest health insurer, and Optum, which among other things runs the nation’s largest physician practice and a leading pharmacy benefits manager, from the hack. And fortunately, because of the nature of Change's business, direct impacts to patient care appear to have been limited and resolved relatively quickly.

That said, policymakers, experts, and even UHG executives—which are working with the FBI and a laundry list of elite cybersecurity and tech firms—are still in the early stages of understanding the attack and its full consequences. The incident has roused the attention of lawmakers who are eager to question Witty later this month (and displeased that he or one of his deputies didn’t show for last week’s hearing).

This is not the American health care system’s first crippling cyberattack, of course. Data from HHS shows that over the past five years, there has been a 256% increase in large data breaches due to hacking and a 264% increase in ransomware attacks. According to the American Hospital Association, “a serious ransomware attack”—or one in which the hacker demands payment in exchange for an end to the attack—is launched against a U.S. medical provider roughly every other week. Insurers have been targets too: The largest health data breach on record (at least until now) belongs to Anthem, since renamed Elevance—No. 22 on last year’s Fortune 500—when 80 million patient records were compromised in a 2015 hack of the company’s systems.

It’s perhaps unsurprising. The U.S. health care sector, which represents a fifth of the U.S. economy, is a juicy target for hackers given the size of the prize, and the stakes are high for those weighing whether or not to hand over a ransom payment. In addition to ransoms collected, medical records reportedly sell for more than $60 on the dark web, exceeding the price of a Social Security number ($1) or credit card data, which goes for $5.

What happens next?

Amy Graham, a consultant for Stroudwater Associates who works with rural health providers, expects the worst is yet to come in her world, as reserves dwindle and hospital administrators catch up with the fact that they haven’t been paid for many of the services they’ve provided in recent weeks. “If they don't have a good communication with their outsourced vendors or payers, they might not even know that it's happened,” she says, adding it’s only a matter of time before people connect the dots and realize what the Change Healthcare cyberattack has done to their financials.

Many expect the distressed, post-hack landscape to lead to even more consolidation in the health system—the sort that is likely to benefit and grow the gigantic footprint of UHG. There is already at least one case in which Optum has bought up a provider that was pushed to the brink of financial ruin by the cyberattack, a point that has generated much consternation among lawmakers at last week’s hearing. “How alarming is this! I’m at a loss for words,” said Rep. Buddy Carter, a Republican from Georgia who is also a pharmacist. “Mr. Chairman, we’ve got to address this situation.” (According to reporting by the Wall Street Journal, UnitedHealth Group is already the subject of an ongoing federal antitrust investigation.)

Certainly, the cleanup for all parties promises to be difficult and fraught. And at many practices, the usual (elaborate) processes to make sure insurance covers patient care has gone by the wayside. In some cases, physicians have delivered care without being able to check whether the patient’s insurance is up-to-date or obtaining the prior authorization typically required. In other cases, claims are being paid without an “Explanation of Benefits,” giving patients and providers little insight into what was paid and accounting for it.

Some see this as a daunting reconciliation task down the road, while others in the provider community, like Molly Smith, a group vice president for public policy with the American Hospital Association, say they “are very worried” that payers will exploit the situation, skimping on the payment of claims, to “protect their bottom line.” Already, there are a number of lawsuits against UnitedHealth Group over the alleged breach of patient data and the loss of revenue for providers.

For Reinheimer and Martin, payments have finally started to trickle in. That’s not because their Change services have been restored, but because their respective billing firms switched clearinghouses. Still, Reinheimer said when we spoke again in mid-April, “There are all these questions, and nobody’s answering any of them. They just keep delaying timelines.”

Amazingly, despite the ongoing post-hack headaches, things are more or less on track financially at UnitedHealth Group. On its first quarter earnings call last week, the company actually reported better than expected results. The cyberattack cost the company $872 million this quarter due to restoration efforts and lost business, but of course that’s just a blip for a company that reported $99.8 billion in revenues in the same period, $8 billion more than last year. (For the whole year, UHG expects the cost of the hack to range from $1 billion to $1.6 billion.)

Meanwhile, Roger Connor, the CEO of Optum Insight, assured investors that he has "thousands of people” who remain busy working on other products and the company’s “innovation agenda.”

Investors may have been reassured, but Jolley, of the American Economic Liberties Project, was not. What does it mean when a company is so massive that it’s barely impacted by the unprecedented, system-crippling attack launched on its own systems? Jolley draws a glum conclusion: “They’re too big to care.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance