The 9 things this top economist has learnt about investing in the last 35 years

AMP Capital chief economist Shane Oliver has seen through Australia’s 1987 recession, the Asian crisis, the dot com bubble, the mining boom, the GFC, the Eurozone Crisis, the end of the Cold War, and now today’s US-China trade spat.

“But as someone once observed the more things change the more they stay the same,” the top economist wrote in a note.

“And this is particularly true in relation to investing.”

Here are the most important lessons Oliver has learnt in 35 years:

1. There is always a cycle

“Droll as it sounds, the one big thing I have seen over and over in the past 35 years is that investment markets constantly go through cyclical phases of good times and bad,” he said.

Some are short, just 3-5 years; others are longer, like the secular swings that go for over 10 or 20 years in the share market.

“Debate is endless about what drives cycles, but they continue. But all eventually contain the seeds of their own reversal,” he said.

There’s no such thing as new eras, paradigms or new normals, according to Oliver: all things must pass.

“What’s more share markets often lead economic cycles, so economic data is often of no use in timing turning points in shares.

2. The crowd gets it really wrong sometimes

Remember the huge spike in interest in cryptocurrency in 2017? Cycles in the market often get amplified by investor irrationality, Oliver pointed out, which is rooted in investor psychology and a range of behavioural biases investors fall victim to.

“These include the tendency to project the current state of the world into the future, the tendency to look for evidence that confirms your views, overconfidence and a lower tolerance for losses than gains.

“What the investor crowd is doing is often not good for you to do too.”

Investments or assets that are traded in a state of euphoria aren’t bound to last long.

“So, the point of maximum opportunity is when the crowd is pessimistic, and the point of maximum risk is when the crowd is euphoric.”

Related story: Your news-reading is hurting your investments

Related story: 8 volatility lessons all Aussie investors need to know

Related story: 6 things investors are worried about... but shouldn’t be

Related story: The investing apps you need to know about

3. What you pay for an investment matters a lot

This one can be summed up straightforwardly: “the more you pay for an asset the

lower its potential return, and vice versa”.

Yesterday’s winners are often tomorrow’s losers because they become overvalued and overlooked, Oliver pointed out.

“While this seems obvious, the reality is that many find it easier to buy after shares have had a strong run because confidence is high and sell when they have had a big fall because confidence is low.”

4. Getting markets right is not easy

Things seem obvious in hindsight: that boom was sure to go bust, that investment was sure to take off. But no one has a crystal ball.

Best rule of thumb? “Usually the grander the forecast – calls for “great booms” or “great crashes ahead” – the greater the need for scepticism as such calls invariably get the timing wrong (in which case you lose before it comes right) or are dead wrong,” said Oliver.

The predictors may get it right one day, but until then, they could be losing a lot of money in the interim, the top economist said.

“The problem for ordinary investors is that it’s not getting easier as the world is getting noisier as the flow of information and opinion has turned from a trickle to a flood and the prognosticators have had to get shriller to get heard.”

5. Investment markets don’t learn

Oliver says he sees investment markets make the same mistakes over and over, even though after each bust everyone swears it won’t happen again.

“But it does! Often just somewhere else. Sure, the details change but the pattern doesn’t.

“As Mark Twain is said to have said: ‘history doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes.’” After time, collective memory dims, Oliver said.

6. Compound interest is magic

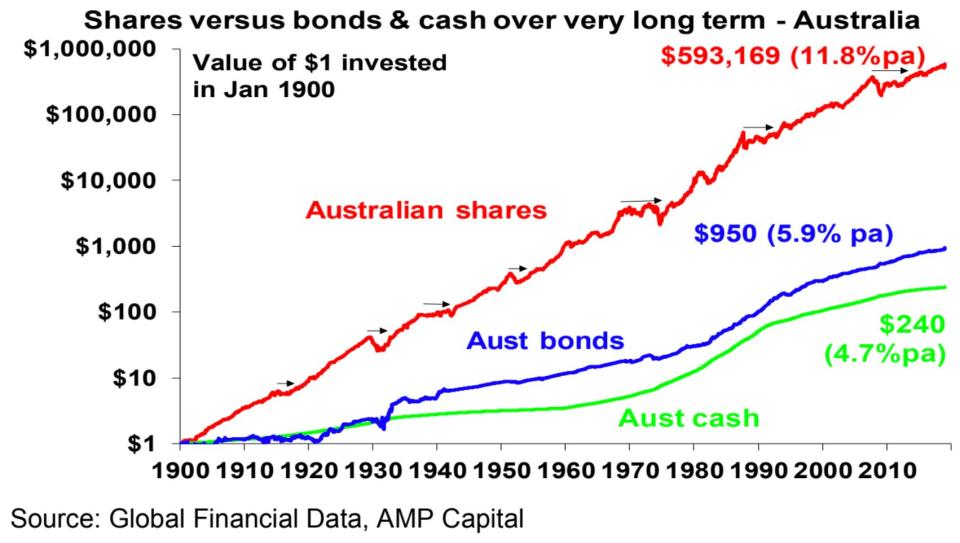

The lesson can be simply distilled into the following: “The impact of compounding at a higher long-term return is huge over long periods of time.”

If you’d invested a dollar in Australian shares in 1900, you’d have $593,169 today, Oliver said.

7. Optimism pays off

“If you don’t believe the bank will look after your deposits, that most borrowers will pay their debts, that most companies will grow their profits, that properties will earn rents, etc then you should not invest,” said Oliver.

If you get too hung up about the next two or three years tanking, you’ll miss out on the seven or eight years when it rises.

8. Keep it simple, stupid

Investing is complex enough – and then we go and complicate it with more information, apps, platforms, rules, and regulations, according to Oliver.

If you spend too much time fretting about second-order stuff, you’ll ignore your portfolio’s key performance driver.

“So, it’s best to keep it simple, don’t fret the small stuff, keep the gearing manageable and don’t invest in products you don’t understand.”

9. Know thyself to succeed at investing

Smart investors know their psychological weaknesses and proactively manage them, Oliver noted.

To do this, you can take a long-term approach to investing, he said. “But this is also about knowing what you want to do.”

Regular trading or an SMSF may work if you want to take a day-to-day role managing your investments, but it will require a lot of effort and time. If you haven’t got the time, then it’s best to use managed funds.

“It’s also about knowing how you would react if your investment suddenly dropped 20 per cent in value.

“If your reaction were to be to want to get out then you will either have to find a way to avoid that as you would just be selling low and locking in a loss,” Oliver said.

“If you can’t, then you may have to consider an investment strategy offering greater stability over time (which would probably mean accepting lower returns).”

Make your money work with Yahoo Finance’s daily newsletter. Sign up here and stay on top of the latest money, news and tech news.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance