'We keep pushing forward': The story behind Tim Anderson's promise

One day his daughters will be ready for his story. They’ll be old enough. Wise enough. Courageous enough. The people they know and love, even those they only sense, will fit into their places. One day. Though, the truth is, Tim Anderson Jr. is still sorting through some of that himself.

He has time. They’re so young. He is, too, just 26. The story’s still gathering characters, scenery, meaning.

One day they’ll laugh and cry in all the places their dad laughed and cried, and they’ll understand why he is him, and then why he believes in them with all he has. They will be beautiful and strong and smart like their mother, and when their dad and mom teach them about beauty and strength and intelligence, those lessons will be about compassion and forgiveness, too. And loss. And loneliness. And dignity. And getting by, best they can. The mistakes people make simply because they are people, then maybe make them again, well, then other people decide to turn their backs or come closer.

See, just as right and wrong get blurry in the moment, so does judgment in the aftermath, in the years spent living with the consequences, in the decisions to love. Or not. That makes the man. That makes us all.

“I made a promise,” Tim Anderson Jr. said, “that I will always be there for my kids.”

To them, he made the promise. To his wife, Bria. To himself. While that would seem the barest of the parenting minimums, it’s not. It might even be the holiest of the promises. To understand its strength, its power, its potential, they must only understand his story.

One day.

Nearly 16 years behind bars

Tim Anderson Sr. would awaken on those weekend mornings, sometimes it was a Saturday, others a Sunday, before everyone else. He would wait for the door to open. He would shower and shave, then dress in his cleanest clothes. Eight-thirty would come slow where they measured time not by days or months or years, certainly not by hours, but by an adherence to — a commitment to — the routine. No sense in counting. Someone else did that.

On those special weekend mornings, Tim Anderson would reach for fragments of his pattern, small pieces of it that wouldn’t stick, all out of order. A few pages of a James Patterson novel he’d just have to re-read later that night. Tupac, on his headphones, promising, “Everything gonna be alright,” and Tim would just have to take his word for that.

Not that he didn’t believe him. He did. He had to.

When Tim Anderson met his son, Tim Jr., they were separated by a pane of glass. That particular window, along with the walls that held it, the steel bars behind it, the fences that encircled it and the men who stood where the walls and bars and fences lacked sufficient authority, came with a 188-month sentence for trafficking in cocaine. Along with poor judgment and illegal possession, he had been guilty of bad timing. Crack was the devil’s drug. Congress treated it as such, and then some. For his pocketful, Tim Anderson, a first-time offender, would do nearly 16 years. The door closed behind him in May 1993. His son was born a month later.

Therefore, the window, his own reflection laid over mother and child, and a tapped hello.

Through the glass

Tim Anderson Jr. would awaken on those weekend mornings early, almost like a school day. His aunt, Lucille Brown, the woman he called Mom, would have him fed, dressed and waiting on his great-grandfather, George, by the time the car slowed out front.

The drive was almost two hours out of Tuscaloosa. The years passed and pretty soon Tim-Tim — everybody called him Tim-Tim — would graduate from the back seat to the front seat. Then his feet would touch the floorboards. On one of those mornings the flip-down sun visor would cast a shadow across his face. Those drives always took them — Granddad George, Tim and Tim’s sister — east, into the new day. Until Tim was in first or second grade, they’d driven to Talladega, to the prison there off Alabama state route 275. After that, to Montgomery and the minimum security camp where the visitors’ room vending machines had chicken sandwiches and juice boxes. The cupboards had Uno and Monopoly.

They passed the miles and the years talking about school and basketball and baseball, and then finally Granddad George would tell stories about Tim’s dad, what he was like as a boy, born in Tuscaloosa, moved to Los Angeles, then to Las Vegas, but always came home to Alabama in the summers. Tim’s dad was a ballplayer too, then fell in love with music. He was a drummer, first in the marching band, in those drum lines, and then in jazz bands. He was an entrepreneur and was good with his hands; all the Anderson men were, they had a sense for those things. He and Tim’s mother, his blood mother, met young.

Then one day she’d stood on the other side of that glass and held up her boy, their reflection laid over her boy’s daddy.

How Tim Anderson chose baseball

On June 9, 2016, 11:16 pm in Tuscaloosa, Terrance Dedrick’s phone pinged. He’d worked all day. He was in bed.

“Call me.”

Tim-Tim.

Terrance thumbed the number. Half-a-ring.

“Bro, I’m being called up. I’m not supposed to tell anyone.”

They’d been friends for as long as they could remember, from the church gyms and sandlots to the first time getting real uniforms, from the Lil Wayne-heavy mixtapes to the party where shots rang out and Tim-Tim ran down the street and straight out of his new Jordans, to the long drives in the back seat of Mama and Papa Dedrick’s Toyota Sequoia. The Dedricks always drove to the high school baseball games. They cheered their son and the sons of the boys whose moms and dads couldn’t be there, and especially Tim-Tim, who was quiet and polite and could really play.

Tim had transferred into Hillcrest High School before his junior year, a basketball player who’d twice broken his leg and therefore had given up on baseball. Terrance, a pitcher and first baseman entering his senior season, urged him to attend tryouts. Tim said sure and then didn’t show up. Terrance arranged for another tryout, just Tim and the coaches, and pleaded with Tim to show up.

Tim was raw but unmistakably talented. At the end of the tryout, the head coach told him he’d made the team as far as he was concerned, but the final choice would be left to the team’s seniors. Terrance was not just a senior, but team captain. Terrance had felt he was more than a friend to Tim, but a big brother. He was on the team. In Tim’s first game, Hillcrest High Patriots at Central High Falcons, he played left field, but did not hit. The pitcher hit for him.

Terrance graduated at the end of the season and played baseball at Shelton State Community College, where he told the coaches about a player a year back at Hillcrest High. Then Terrance went to Auburn, where he told those coaches about a shortstop at East Central Community College in Decatur, Mississippi.

There were never enough spots on the roster or scholarships available, so Terrance and Tim-Tim did not play together again. But on the morning of June 10, 2016, Terrance walked into the offices of Dedrick Wealth Management Group, told Papa Dedrick — Thomas Dedrick — about the text message he’d received late the night before, and later that morning they boarded a flight to Chicago. Tim-Tim would be starting at shortstop for the White Sox that night. He’d get two hits.

On a warm, breezy night at what was then U.S. Cellular Field, Terrance might have recalled another phone call from a few years before. He was standing in the gym at Shelton State. Tim-Tim was on the phone, telling him he was thinking of giving up baseball, playing basketball instead, maybe his future was there.

Naw, Terrance told him, you know about those 6-foot-6 guards out there, right? Thing is, man, he told him, you are good at basketball. No doubt. But you can be great at baseball.

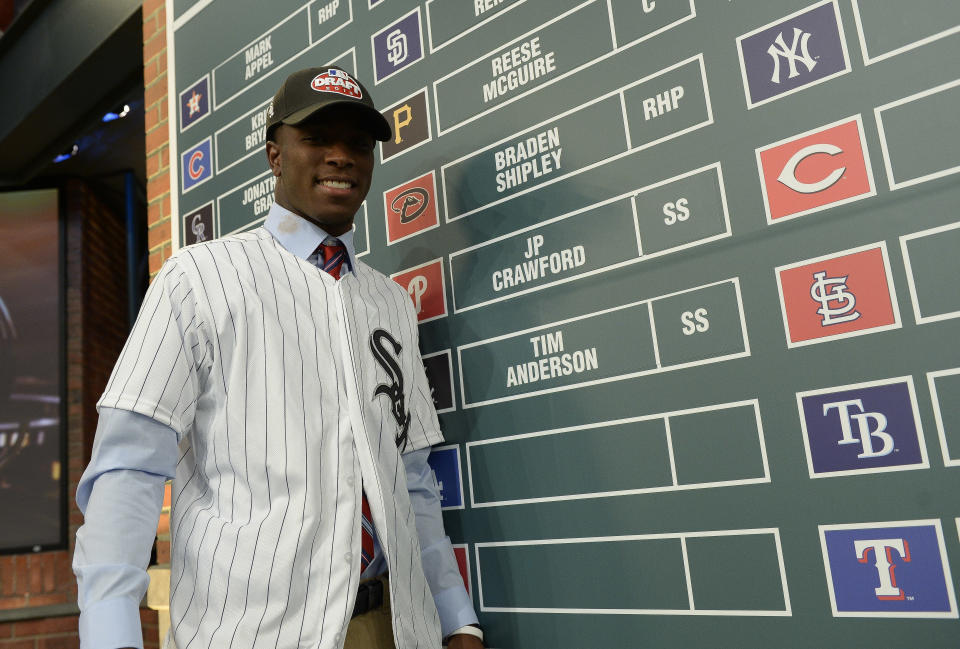

Tim-Tim hit .495 that season at East Central and in June was picked in the first round of the draft by the White Sox. He signed for more than $2 million.

‘He never judged me’

When 3 o’clock came, when the Monopoly money was laid in the proper compartments and the sandwich wrapper and juice box were thrown away and the chairs raked against the floor and the other families were saying their goodbyes, Tim Sr. would hand his camera to Granddad George or a fellow inmate and pose with his son and daughter. Every time. When the pictures came back, he’d peel away the plastic on the next page of a brown and gold album, square the photo so it lined up even with the top and sides, then smooth and pat down the plastic.

He stored the album near his bunk. When the days were done, when he’d finished working the kitchen or the leather shop or studying for his commercial driver’s license or chasing fly balls in the yard, he’d open the cover of his photo album, turn the pages and watch his boy grow up.

“How you doing, baby boy?” and hit send.

“Good. I love you.”

“I love you too.”

“See you soon.”

Young, dumb, a little money in his pocket, he’d messed up back then. Messed up real bad. The cost was four walls, almost 16 years out of the middle of his life, his children raised by kind and generous folks who weren’t their parents, God bless them, and a couple weekend days a month when time actually moved.

When the nights were bleakest, barest, rawest, he wondered how to cover that distance when the sun rose. How to connect with a son he didn’t raise. How to fill the time when the regret came. How, one day, he’d have to replace the layers of memories, the ones he was left out of, with something else. How to make sense of a world he’d created himself, for him and for his boy. He’d go through those pages again, his boy in his arms, his boy tottering beside him, his boy with a gapped smile, his boy with shoulders broadened and growing, his boy then eye to eye with him, as though the dad was a door jamb marked with dates and pencil scratches.

He said that on birthdays and Christmases and every month he sent money, earned in prison, some by selling purses he made in the leather shop. He figured the money went for school clothes or something useful, maybe uniforms for games he’d never see.

“You should know,” Tim Sr. said recently, “Tim went through a lot growing up. Mentally. Right? Over the course of the years. Think about it. Your dad’s gone. Your mom, too. A lot going on. In your mind, you couldn’t figure it out. But you don’t want to figure it out. Year after year, not understanding. Me, his mom. To go through all that and then to overcome it. Then, you get older — 21, 22, 23 — you start asking these questions. He had a time when he was just dark. For him. You could never see it in him. But I could. Because we’re the same way. I could see it in him because I know me.”

Tim Sr. was quiet then. He’d come home those years ago and they’d sat together on a front porch in Tuscaloosa. He’d wanted to walk, to see the neighborhood, to feel it on his skin again. The ankle monitor kept him on the porch. His son told him he loved him, he was glad he was home, they could start over.

“He never judged me,” the father said. “Never. Never faulted me for anything I done.

“For him to go through all that, turn out a great guy, I gotta take my hat off to him. He turned out great. And he’s my son.”

Soon as he could leave the porch, he taught his son to drive, behind the wheel of his grandmother’s Grand Marquis. When the timing was right, Tim Sr. handed his son that brown and gold album. They grew up again together, got back to today, and cried a little over that, Tim Jr. almost as old as his dad is in the first pictures, so long before, the reflected images of themselves lingering still.

That’d be the tidy end to the story. Except Tim Sr. returned to jail for 14 months, from early spring 2017 to late spring 2018, for possession of marijuana.

“That was a situation of mine,” Tim Sr. said.

‘Let him in on it’

The tidier end to the story is Tim Jr. sitting in a small office at Camelback Ranch, outside Phoenix, his smile wide and his heart full.

He is married to Bria. She taught high school English, has her Master’s degree and is working toward her PhD. They have two young daughters, Peyton and Paxton. Tim and Bria co-founded League of Leaders, a foundation that honors the memory of Tim’s best friend, Branden Moss, who was killed in a shooting nearly two years ago in Tuscaloosa. The charity seeks to assist needy children in Chicago and Tuscaloosa, including providing school supplies and back-to-school haircuts. Tim knows their stories, and they his, without having to ask.

He won a batting title. Nine years after a pitcher hit for him in his first high school baseball game, Tim Anderson batted .335 for the White Sox in 2019.

He is, perhaps, the spiritual soul of a franchise intent on becoming relevant again, he being young and charismatic and mindful of the world, he being a terrific shortstop who plays the game as though he enjoys it, he being a black man from the South, he being desperate to offer his hand to those whose immediate futures look a little like his distant past.

His father lives in a suburb north of Los Angeles. He is married to the actress Shun Love Anderson. He dotes on Peyton and Paxton. He drives to Phoenix to watch baseball, to catch up on the layers of memories that are back there somewhere, to watch his boy play.

“It’s only about seven hours,” Tim Sr. says.

It would look like a fresh start if you didn’t know better, if you didn’t know about the text messages and those early-morning drives on those Saturdays and Sundays and the son who wouldn’t ever give up on his dad. Not the first time. Not the second time. Not ever. On an afternoon at Camelback Ranch when he’s talking about a whole lot of life crammed into 26 years, he laughs and holds up his phone, where someone in the world named Dad has sent a message, “How you doing, baby boy?”

“We don’t worry about the past,” Tim-Tim says. “We keep pushing forward. All we can change now is the direction we’re heading. We can’t change back there, so there’s no sense in worrying about it. But we can talk about it. We’ve talked about it. And kind of understand the situation. Understand his situation. Understand my situation, where I was at the time … So it’s all about communicating and being open and, man, we just sat down and laid everything on the line.

“One cut,” he clapped his hands, “this is what it is, all right, now let’s move forward. And our relationship is great. I can call him right now and he’d be the happiest man in the world. ‘Hey, whatcha doin’ man?’ He’s almost like my brother now.”

And maybe that is how a 47-year-old man connects with the 26-year-old son he did not raise. He becomes something different. He accepts what he was not a part of. If not entirely, he understands it. He makes peace with it, amid all the hours of peace. Amid the routine. And the son says OK.

“Now that I’ve experienced it,” Tim Jr. says, “I get to pour into him my positive energy. He doesn’t have to worry about how I feel. I’m always in the positive state. Trying to stay positive. Trying to keep people around me positive, man. And, man, life’s tough. Life’s tough. We go through so much every day. Every day. So I just try to drive a positive line and try to stay away from negative energy and try not to let that rub off on me.

“He always said ‘I love you.’ That was enough for me. When you’re going through that, not many people would say that. I love you. You know? And when I would talk, he would listen. Not many people would hear me out. But when I would sit with him or have a conversation with him, he would actually listen … We’re all human. We make mistakes. We make them twice. We make them three times. You know? And it goes on and it goes on. You can’t hold grudges on people. You got to continue to move on, man. Life’s so short. You don’t want to hold that grudge. I don’t want to feel like that.”

Maybe it wasn’t perfect. Maybe it won’t ever be. Tim Anderson got over perfect a long time ago.

There were, however, great days. He remembers them as great. Maybe not all of them. Enough of them. His dad rubs out the goosebumps in his arms even thinking about them, conjuring those weekend mornings when his children walked through that door, Tim-Tim more like a man every time, and then one day he actually was one.

It left him with a duty. He would return those years to his dad. Their names are Peyton and Paxton. They draw and they like stories and they run around and they laugh. They call him GT, short for Granddaddy Tim, because GT is easier to remember and doesn’t sound as old.

“Let him in on it,” Tim Jr. said. “‘Hey, c’mon, watch this. You’re going to live this with me. You’re going to come over here, hang, see the kids play. You’re going to live this with me. Something that you wanted to do, how you wanted it, and now I have it how you wanted it. So come and enjoy this with me. Watch my kids grow.’”

More from Yahoo Sports:

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance