Textbook giant doubles down on digital, promises lower prices for students

For many cash-strapped college students, the decision to buy a new or used textbook is a hard one, since older — and cheaper — editions may miss out on key concepts or even chapters.

However, newer textbooks are exceedingly expensive.

Textbook giant Pearson (PSO) hopes to diffuse that dilemma, announcing this week that it will make all future revisions to its textbooks digital first, while clamping down on the secondary used textbook market, CEO John Fallon told Yahoo Finance.

“This has been something that has been changing gradually over the years,” Fallon told Yahoo Finance in an interview. “We had something like a 34% increase in sales of ebook volumes last year. … going digital has been something that's been happening over a long period of time.”

The 175-year-old British company said that moving forward, every time there’s a revision to a textbook among 1,500 of its active U.S. titles, it will be issued online first and updated on an ongoing basis. Students are expected to pay up to 30% less, Fallon said, with e-books costing $40 on average and $79 for a “full suite of learning tools.” Students who want a physical copy can still rent a print textbook from Pearson for $60.

“Major textbook publishers have operated on an unsustainable model on the backs of students for years,” Nicole Allen, Director of Open Education at the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition, told Yahoo Finance. “Textbook revisions too often were driven by the profits associated with new additions as opposed to updates to the content, and in that sense this change is a step in a better direction. Whether it will turn out better for students remains to be seen.”

Previously, Pearson would revise the textbook every 2 or 3 years, create a new print textbook, and follow that with a digital update. With this new production model, that process of updating will continue, but the digital update will come first — meaning students with the e-book can see revisions first — and if needed, could buy the print version.

“In a in a digital first world, it makes sense to flip that model,” said Fallon.

Pearson wants to ‘lower the price to students and … increase Pearson’s revenue’

Pearson’s revenue has been falling over the past few years, and it has cut thousands of jobs and offloaded various assets like the Financial Times and the Economist, trying to pool resources to fix its textbook business.

The U.S. textbook market has become one unit that Fallon is trying to turn around.

“The annual sales in this part of our business and in higher education course is about $1.3 billion. That is just over 20% of Pearson’s total revenue,” said Fallon. “The business has been declining in recent years. … what we're trying to do here is to get to a point where we can stabilize the business and it does grow again, but we grow by adding a lot of extra value to the students, and make it less likely that they feel the need to participate in the secondary market.”

The secondary market — used textbooks — has been a pain point for the company.

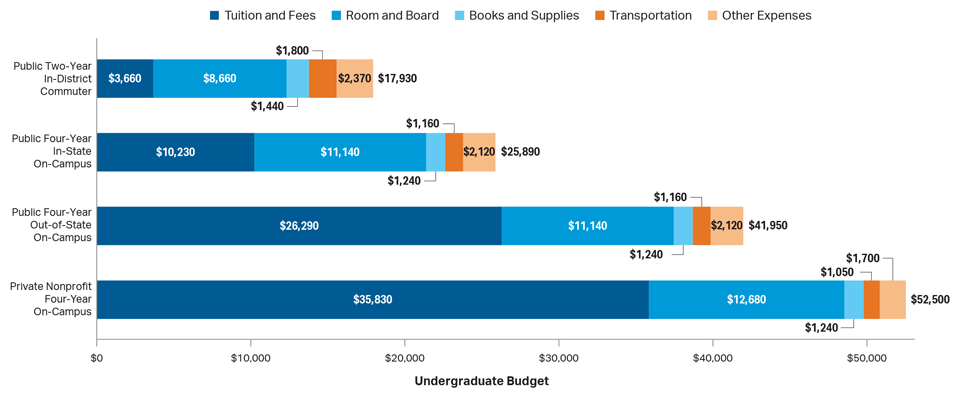

In the U.S., the average cost of a textbook has been climbing over the years, and an average student is likely to spend $484 on required course materials, according to the National Association of College Stores. Over the course of their college education, “books and supplies” are expected to cost them more than $10,000, according to The College Board.

Hence many college students often opt to buy older editions to save money. But that decision deprives Pearson of revenue.

Fallon believes that the digital offerings, which in theory would require students to purchase the e-books or other tools to access the textbook, would kill two birds with one stone: Students would save money and time — since they only need to buy one textbook that automatically updates — and Pearson stops them from dipping into secondary markets.

“If we can provide better value at a lower price to students, which is what this enables us to do, …. we can lower the price to students and actually increase Pearson’s revenue,” stated Fallon.

SPARC’s Allen expressed skepticism: “Just because textbooks are ‘digital first’ does not necessarily make them a better deal for students. Students have relied on the secondary market for savings, and this shift seems designed to take that option away.”

Access codes

Corroborating Allen’s point is that going digital hasn’t helped bring down the overall cost of textbooks overall.

With access codes slapped on digital textbooks, quizzes, and other learning tools that are in some cases made mandatory by college professors, some students have said they’ve dropped classes to avoid the extra charge, opting for a course without the bells and whistles.

“Most of the times I’ve had to buy things that are in core classes,” UPenn student Kenan Saleh, who also wrote an op-ed against e-textbooks in his school paper, told Yahoo Finance in a previous interview. “They make it part of your grade to answer the questions that they have. The online ones are particularly egregious. I never understood those.”

“The problem isn’t digital,” added Kaitlyn Vitez, higher education campaign director at PIRG, a consumer advocacy organization. “The problem is that closed expiring access to materials. When we think about these short-term access codes, or short-term online rental e-textbooks, students can’t retain them or resell them and make their money back.”

Fallon dismissed these issues, saying that Pearson’s products necessitated access codes since the services were high-quality and personalized.

“The access code is giving you access to a MyLab or mastering course, where it is personal to you, and you are submitting your homework online and the Pearson is marking your homework, providing you with the feedback, providing the scores that you got to your teacher or your faculty,” explained Fallon. “So you are actively engaging, and we are having to do things that obviously costs money, to provide that feedback and provide that support and provide that service.”

In any case, “if you had a three month subscription to Netflix, you wouldn't expect to be able to still have access to Netflix 10 years later,” added Fallon. “You have to continue to pay for the service. And we are providing a service, because we are facilitating between the student and the University.”

He stressed that the corresponding investment into improving that service was sizable.

“Across the company, we are investing just under a billion dollars a year in the research and development of new products and services,” Fallon said. “We're also determined to provide good value to our students in a way that provides a good and sustainable return for our shareholders as well.”

—

Aarthi is a writer for Yahoo Finance. Follow her on Twitter @aarthiswami.

Read more:

Presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg: ‘I have six-figure student debt’

Bernie Sanders unveils sweeping student debt cancellation plan

Over half of parents willing to go into debt to pay children’s college tuition

Elizabeth Warren unveils 'broad cancellation plan' for student debt

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance