Six big questions on the global vaccine response, answered

Why do we need a global response?

In the nine months since the global vaccine rollout got underway, health workers have administered more than 4.7 billion Covid-19 vaccines. At home, the UK vaccination rollout has been a phenomenal success and has saved countless lives. But this remarkable achievement is overshadowed by a colossal challenge – nearly 69 per cent of people worldwide still have not had a single dose of the vaccine.

There is a striking gulf between vaccination rates in different countries, with just 1.3 per cent of people in low-income countries fully vaccinated. Dozens of countries, particularly in Africa, have barely started their inoculation campaigns.

The truth is this: while the wealthiest among us are booking nights out in restaurants or summer holidays on the beach, the virus continues to rampage through poorer countries.

Kenya, for example, expects that by 2023 it will have just 30 per cent of its population vaccinated, and that’s with the vaccine sharing facility COVAX covering the first 20 per cent. That long wait would give the virus time to spread.

Failure to address inequalities is not just a moral issue, it is a practical one. Without a fast and fair global rollout, the virus will find new vulnerable populations and continue to spread. It does not respect borders and will not be eradicated by sporadic vaccination coverage across different populations. It will replicate and mutate into new and unpredictable forms that can ricochet back to us.

Ending the pandemic requires an unprecedented level of international cooperation. Millions of lives - and our own recovery - are at stake.

What can wealthy nations do?

The world’s richer countries have pledged more than £4.2 billion to COVAX, the global effort to supply vaccines to the developing world at little or no cost. But that’s a small fraction of what wealthy nations have spent on themselves and many of the pledges have not been fulfilled.

Some people say COVAX has not moved quickly enough. Initial targets were missed and problems with deliveries have been exacerbated by the calamitous surge of infections in India.

COVAX has also found itself in competition with individual countries doing direct deals with pharmaceutical companies, putting extra pressure on the available supply of vaccines.

Today, COVAX is 190 million doses short of where it needs to be. Countries like the UK and other G7 nations which have secured the majority of existing supplies and are the only ones who can makes doses available right now.

The Wellcome Trust and Unicef have called on the G7 together to commit to sharing 1 billion doses over 2021 and to increase funding to distribute vaccines. President Joe Biden has pledged that the United States will purchase half a billion Pfizer vaccines for poorer nations and the UK has announced it will donate at least 100 million surplus Covid vaccine doses to other countries in the next year.

Developing countries have also demanded that rules protecting vaccine patents be relaxed to allow them to increase production.

In May, the United States voiced its support for a temporary lift of patents on vaccinations. But some producers argue that waiving patents alone wouldn’t solve much, saying it would be like handing out a recipe without the ingredients or instructions. And while waivers on patents are one step towards opening up more production, it doesn’t resolve the problem of limited manufacturing capacity.

What are the biggest vaccine supply challenges?

In the early days of the pandemic, when companies were just beginning to develop vaccines, placing orders for any of them was a risk. Richer countries could afford to spread that risk by placing orders for multiple vaccines, reserving doses that smaller countries may have otherwise purchased. Most wealthy countries pre-ordered enough vaccines to cover their populations several times over, while poorer ones had trouble securing any doses at all.

But nationalism and buying power are only part of the story. There is also the sheer difficulty of making so many doses.

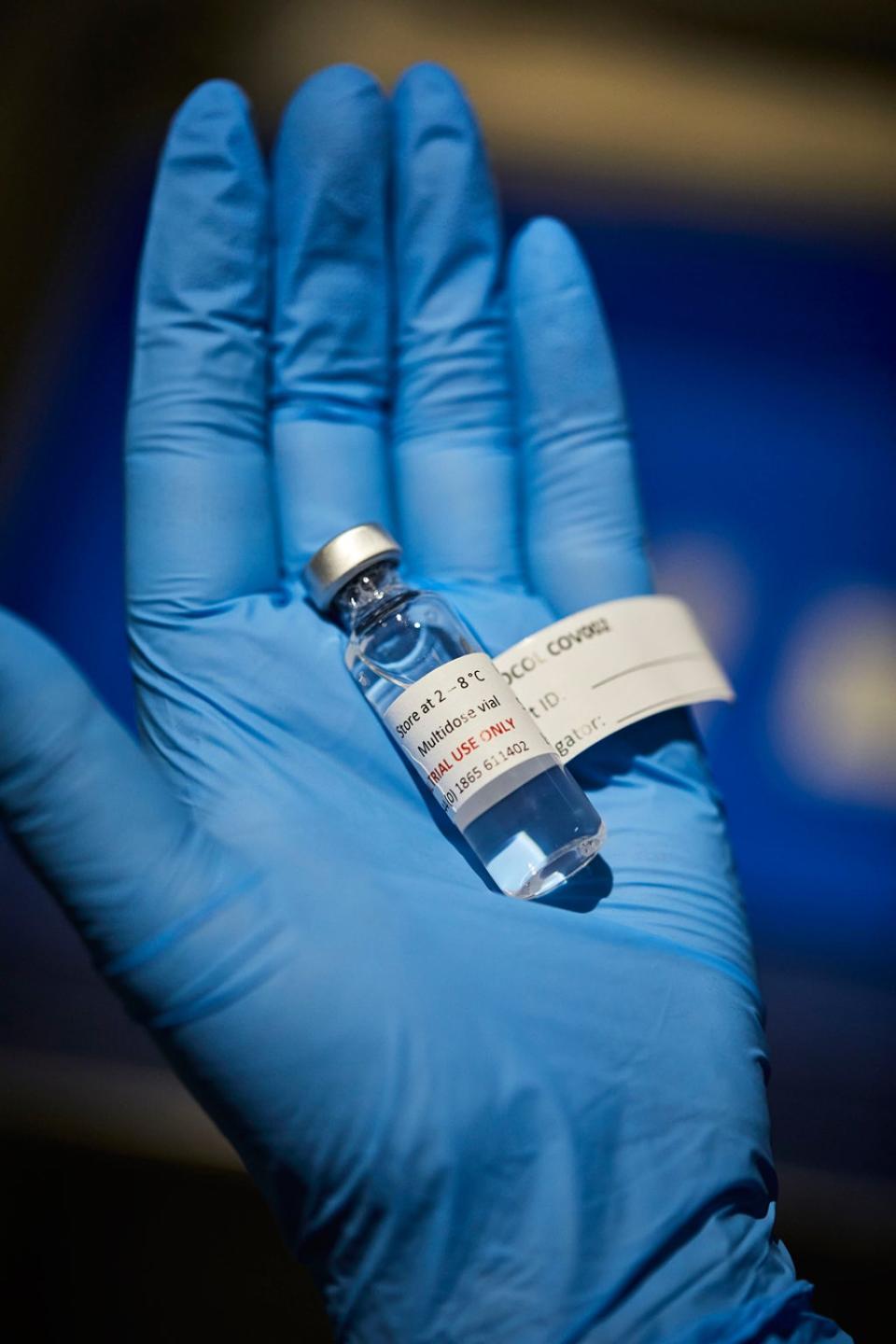

There are only so many factories around the world that manufacture vaccines and only so many people trained in making them — and they were busy even before the pandemic. Likewise, production capacity for biological raw materials and filters, bags, glass vials, stoppers and syringes is also limited. Supply chains on this scale usually take years to establish.

The world’s largest vaccine maker, the Serum Institute of India, projects an output of one billion AstraZeneca doses this year, on top of the roughly 1.5 billion doses it makes annually for other diseases.

One solution in Africa could be local manufacturing of vaccines, but there are significant hurdles. Right now there are fewer than 10 African manufacturers with any vaccine production capacity and they are based in five countries: Egypt, Morocco, Senegal, South Africa and Tunisia.

Most African countries are supplied with vaccines by Unicef supported by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Fewer than 10 countries are self-sufficient in terms of vaccine procurement. This presents challenges when trying to establish sustainable vaccine industries in Africa which would ideally require advance purchasing support from African governments. Most countries don’t buy their own vaccines and therefore cannot commit to buying them locally.

What is the vaccine situation in Africa at the moment?

Africa has the slowest COVID-19 vaccine rollout of any continent and less than 2 per cent of the continent’s nearly 1.3 billion people has received even one dose. Meanwhile, African countries are battling a third wave of Covid-19 infections, the World Health Organization (WHO) warned, and weekly COVID-19 deaths in Africa reached a record peak in the first week of August.

African health officials say they aim to vaccinate at least 30 per cent of the population by the end of the year. But supplies of the AstraZeneca vaccine from COVAX, which have made up the bulk of jabs distributed on the continent so far, have ground to a halt after India blocked exports by the Serum Institute to battle its own outbreak.

African countries are struggling to find supplies both for first doses and for second doses for those who had already had their first jab. The continent’s best performers - like Rwanda and Ghana – have only managed to administer fewer than three doses per 100 inhabitants. (In comparison, the UK has given 129 doses per 100 people).

The continent’s youthful population - the median age is 19 – has thought to have contributed to a comparatively low death toll in Africa. Officially about 120,000 Africans have died of Covid-19, though that may significantly underestimate the true number. Some estimates suggest excess deaths in Africa may be as high as 2.1 million.

Stretched resources, especially a lack of oxygen and intensive care facilities, mean the mortality rate among hospitalised patients in Africa is roughly 20 percentage points higher than any other region of the world.

How can we get the vaccine to everybody?

An important aspect of vaccinating the world is the cost of actually delivering the vaccines. It is estimated that for every $1 a country or donor government invests in vaccine doses, they need to invest $5 in delivering the vaccine.

Reaching people in remote areas and maintaining cold storage supply chains is not easy. That’s why the AstraZeneca vaccine, the so-called workhorse of the vaccine rollout, is so important in difficult-to-reach areas. It is more stable than other vaccines and can survive at normal fridge temperatures.

African countries must ramp up actions to swiftly roll out the vaccines they have, says the WHO. Twenty African countries have used less than half of the doses they have received from COVAX.

Upfront investments in frontline health workers are crucial, especially funding and training health workers—largely women—who administer vaccines, run education campaigns, connect communities to health services, and build the trust required for patients to get vaccines.

For these investments to work, they must pay, protect and respect women frontline health workers and their rights—a cost that is largely overlooked in WHO estimates on vaccine rollout costs.

How can we improve vaccine confidence?

Health experts worry that public scepticism over whether to accept the relatively small number of doses African countries have battled to procure could prolong the pandemic.

A study commissioned by the Africa Centre for Disease Control (CDC) on attitudes to the Covid-19 vaccine in 15 countries indicated a significant proportion of people had concerns around vaccine safety.

About 20 per cent of respondents said they would not have the vaccine – from nearly 10 per cent in Ethiopia, Niger and Tunisia to 41 per cent in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Warnings about very rare vaccine side effects have spread on social media, making people wonder why a shot that much of Europe had temporarily rejected was fit for Africans. Those worries compounded fears that Africans were being used as “guinea pigs” and that the shots would affect fertility.

South Africa, the hardest hit country on the continent, delayed the rollout of the AstraZeneca vaccine. The Democratic Republic of Congo, where vaccine hesitancy is high, has returned 1.2m doses of the shot to COVAX after deciding not to use it.

Health authorities in Malawi incinerated nearly 20,000 expired doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, saying it will reassure the public that any vaccines they do get are safe.

Professor Heidi Larson, Director of the Vaccine Confidence Project at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine has been investigating vaccine hesitancy on the continent. “There hasn’t been very good communication around these vaccines. It’s been a bit of a desert,” she says. “The focus has all been about delivering the vaccine but when they get to those countries they are not prepared.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance