Money Laundering Detectives Have Been Out at the Pub

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Why did it take media reporting to get Australia’s money laundering investigators to start looking into casino operator Crown Resorts Ltd.?

Shares in the gambling company previously controlled by billionaire James Packer slumped 8.2% Monday after it said the country’s financial-crimes regulator Austrac had started a probe into the handling of “high risk and politically exposed” individuals at its Melbourne casino. The investigation started two months after Nine Entertainment Co. newspapers published a series of articles about the activities of high-rolling Chinese gamblers at Crown’s properties.

It’s the latest in a string of prominent cases led by Austrac, after a A$45 million ($32 million) award against racetrack betting operator Tabcorp Holdings Ltd. in 2017, a A$700 million penalty against Commonwealth Bank of Australia in 2018, and a A$1.3 billion settlement with Westpac Banking Corp. last month.

That’s quite a turnaround. For much of its 31-year history, Austrac has been a pretty somnolent organization, tending its ballooning database of suspicious transactions reported by compliance officers without carrying out much of the aggressive enforcement that you might expect.

Just look back at the cases that Austrac has brought over the years. Until recently, the majority of actions involved nickel-and-dime businesses like a pub in southern Brisbane or a cafe in western Sydney.

That’s clearly not going to do the job. Money laundering, by its nature, requires moving large volumes of either physical or digital cash. That means regulators need to be laser-focused on the activities of the companies that trade the largest volumes of those assets — casinos, in the case of notes and coins, and financial businesses, in the case of electronic transactions.

“Until recently they were showing all the symptoms of a regulator who’d been captured by the industry they were supposed to regulate,” John Chevis, an independent anti-money laundering consultant, said by phone.

The string of recent cases shows that things have at last started to change. Paul Jevtovic, a former police officer who took over at Austrac in 2014 before joining HSBC Plc’s compliance department in 2017, pushed the regulator toward a more proactive culture and kicked off the Tabcorp and the Commonwealth Bank investigations.

Still, it’s clear that the agency is some way from being as aggressive as it should be. Last year’s media reports aren’t the first time that public accusations about money laundering breaches have been made against Crown. Independent legislator Andrew Wilkie in 2017 told parliament that casino staff exploited loopholes to avoid disclosing reportable transactions to Austrac (Crown denied the claims).

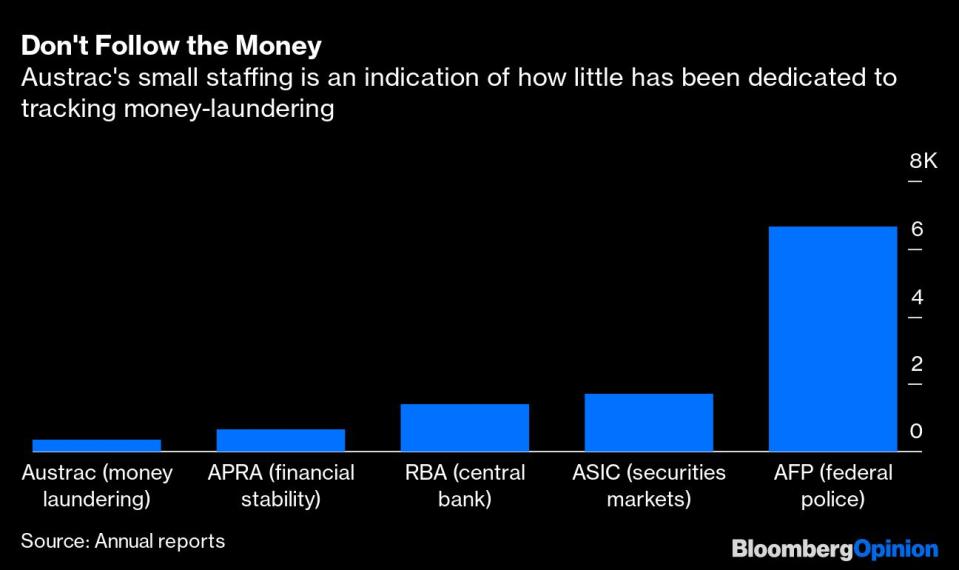

Better funding and collaboration with other agencies would probably help. The number of suspicious transactions reported to Austrac has more than tripled over the past five years, but funding from government and its own paid-for activities is only up by about a third. As it is, the regulator’s relatively small staff is stretched to sort through all the information they’re receiving. Extracting legal penalties from large companies is even more expensive.

Meanwhile, criminals aren’t standing still. The latest avenue for money laundering is probably over- and under-invoicing of traded goods, but that’s even harder to track. Unlike cash laundering, which involves a relatively small number of casinos and financial businesses, invoice-based laundering can take place between almost any two companies in the world.

Austrac’s gradual shift toward a more active stance in recent years is welcome, but it will need to go still further. If you want to hunt rats, it’s no good hanging out in your kitchen. Going down into the sewers may be a thankless task, but it’s the only way to get the job done.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

Subscribe now to stay ahead with the most trusted business news source.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance