Bank investors face a 'conundrum' in an inverting yield curve

The crunch from an inverting yield curve is hurting top-line growth at the big banks, forcing the nation’s largest lenders to turn to capital distributions to deliver estimates-beating earnings per share.

Gloomier expectations in the short run have pushed some of the large banks to temper their forecasts for 2019 in their earnings calls. A big reason: banks are facing higher costs of customer deposits even though the Federal Reserve has signaled no more rate hikes for 2019. Having to pay more on deposits hurts banks’ net interest income, a measurement of revenue made on loans subtracted by interest paid on deposits.

JPMorgan Chase (JPM) CFO Marianne Lake said April 12 there’s a “risk associated with the flat yield curve,” and noted that the company’s $58 billion in projected net interest income for next quarter is no longer “conservative” but “straight down the middle.”

Bank of America (BAC) CFO Paul Donofrio signaled April 16 that their net interest income would only grow by about 3% for the full-year 2019. That figure is roughly half of the net interest income growth Bank of America saw in 2018, at about 6%.

And at Wells Fargo (WFC), executives said April 12 they expect net interest income to decline 2% to 5% this year compared with 2018. The company had previously projected between a 2% decline and a 2% rise in net interest income for the year.

The large banks are already seeing some signs of wear on revenue. Marty Mosby, who analyzes the big banks for Vining Sparks, told Yahoo Finance that an inverting yield curve is creating some pressure that will lead to slower revenue growth.

But Mosby said high returns of capital will allow the big banks to skate by fine even if net income grows only 4% to 5%.

“It’s a different mix,” Mosby said. “We are in a transition from where we saw stronger revenue growth with interest rates going higher to slower revenue growth. But there’s kind of a hand-off to the capital side being able to keep the overall growth high.”

Inversion coming?

The big banks have done just that. The four largest U.S. banks — JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Citigroup (C), and Wells Fargo — bought back a total of $19 billion in stock for the first quarter of 2019.

Through share buybacks and cost cutting, the big four banks were still able to beat earnings estimates on the bottom line.

Keefe, Bruyette & Woods analysts wrote in a note April 18 that while banks are promising estimate-beating EPS, investors face a “conundrum” over the uncertainty of slower growth in the near term.

“[I]n this late cycle economy the best bet would appear to be banks that aren’t promising much growth, but have limited risk of missing earnings,” the KBW note read.

While the large banks get weighed down by macroeconomic factors, KBW says small- to mid-cap sized banks look poised to squeeze higher net interest income and revenue growth.

The future is uncertain with the curve tipping towards further inversion.

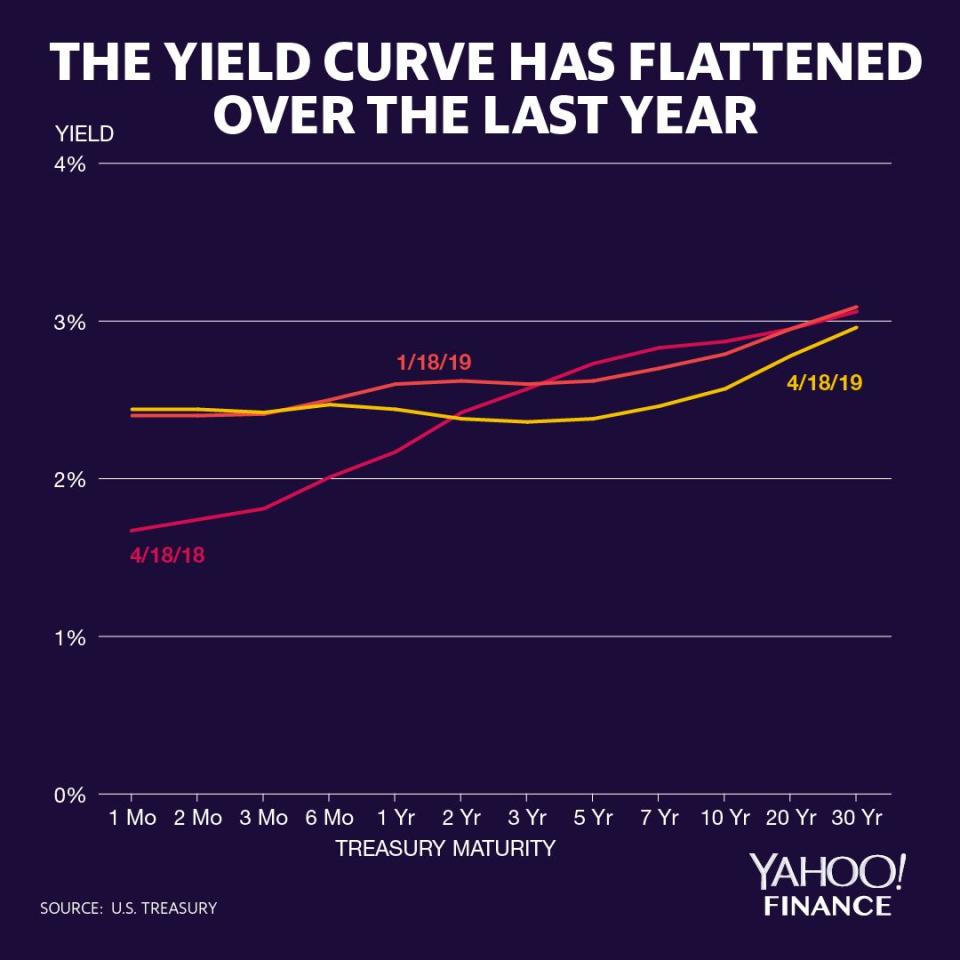

As the Fed raised rates four times in 2018, market participants watched short-term rates nudge higher with little movement in longer-term rates. In December, the yield on the 5-year Treasury note fell below the yield on the 3-year note. In March, the yield on the 3-month Treasury bill slipped below the yield on the 10-year note.

An inversion of the 2-year and 10-year notes — which has yet to happen — has been a bellwether of a recession, although it has generated some false positives in the past.

For now, banks wrangling with the yield curve insist that they can manage their way through whatever comes next.

“The trouble with the yield curve is it can fluctuate dramatically over the short-term and we shouldn't over-interpret or over chase it,” JPMorgan Case’s Lake said on the earnings call.

Brian Cheung is a reporter covering the banking industry and the intersection of finance and policy for Yahoo Finance. You can follow him on Twitter @bcheungz.

St. Louis Fed President on December rate hike: 'It didn't come off very well'

St. Louis Fed President 'hasn't lost confidence' yet in economy

NY Fed's Williams: Yield curve 'not telling us we're about to have a recession'

Myth of Fed 'groupthink' not apparent in bank regulation

Congress may have accidentally freed nearly all banks from the Volcker Rule

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance