How to quit fast fashion without breaking the bank

The UK recently voted on a “fast fashion tax” that would target large clothing producers, with the proposed laws designed to stop large retailers sending waste to landfill and introducing incentives for reuse.

However, the legislation didn’t pass with ministers arguing that current regulations were enough.

Over in Australia, fashion brands are slowly moving to become more ethically and environmentally conscious. But Australians still send an estimated 6 tonnes of clothing to landfill every 10 minutes.

The Rana Plaza factory disaster which killed 1,134 garment makers in 2013 raised another question: in a “buy now” culture facilitated by low clothing prices, how well were garment makers’ treated, and how safe were their workplaces.

They’re questions that stick: According to a UK and US survey of 2,000 shoppers, more than 50 per cent want their favourite brands to act more sustainably.

But, critically, only one third of respondents were prepared to pay more to support brands in moving away from cheap and environmentally and socially harmful practices.

Difficult to fight our fast fashion addiction

It’s a difficult problem to solve, the head of sustainable fashion and textiles at sustainability consultancy firm, Eco-Age, Charlotte Turner admits.

According to a study by PayPal, nearly one in five Australians feel a “fear of missing out” or FOMO, if they don’t buy something when it’s on sale, leading to an average $108 in impulse purchases a month.

A constant sales cycle where new trends are unveiled up to every week with older clothes reduced in price doesn’t help the situation, nor does the fact that online shopping has made accessing these sales so much easier.

Aussies are addicted to online shopping: Here are 8 tips to help you snap yourself out of the cycle

“Living in a society where the ‘new’ is constantly pushed, it can be difficult to change this behaviour,” she told Yahoo Finance.

“Constantly buying cheap clothes is actually a false economy – you are buying clothes which are not designed to last.”

“However, constantly buying cheap clothes is actually a false economy – you are buying clothes which are not designed to last, and in the long run probably spending more than you would on fewer higher quality garments that will last a much longer time, particularly if well cared for.”

This is especially the case for wardrobe staples like coats, jeans and t-shirts.

While customers are used to seeing t-shirts sold for less than $30 and have come to expect that price-point, purchasing a sustainable and more expensive garment would be made from better fabric so the consumer wouldn’t end up lamenting their shrunk shirt.

“It could last significantly longer than a cheaper alternative. Knitwear is another good example – cheaper knitwear is often blended with acrylic, but a pure wool jumper requires less laundering and can be easily repaired if needed – plus it is better for temperature control when the weather changes.”

Developing a personal style

Australian app, GoodOnYou supports shoppers in making sustainable decisions by rating brands and providing information about their practices. It launched in Australia in 2015 but has since rolled out to Europe and America.

“It doesn’t mean giving up on fashion.”

According to CEO Gordon Renouf, switching mindsets about what it is to be fashionable is also key when it comes to quitting fast fashion without breaking the bank.

“It doesn’t mean giving up on fashion,” he told Yahoo Finance.

Rather, it’s developing a personal style that isn’t reliant upon seasonal and even weekly trends.

And, he added: “It’s not only about how they’re made, it’s where they go. Stop buying things you won’t wear.”

Shoppers need to ask themselves how often they will actually wear the item and if it fits their existing wardrobe. It’s about buying clothes for the person you are - not an imaginary version of yourself.

Detaching from social media expectations

Another study from charity Barnardos found around three in 10 women consider clothes old after wearing them less than three times.

And one in seven said being pictured in the same item on more than a few occasions was also a “fashion no-no” and contributed to their decision to turf the item.

“Social media and fast fashion certainly have a large role to play in this idea that constant newness is the norm, but social media can be a force for good,” Turner said.

Bombshell Bay Swimwear is beautiful: It’s also eco-friendly and socially conscious. Here’s how founder Emily Doig does it.

“Firstly there are a large number of companies and organisations promoting a slower lifestyle, and hashtags like our Eco-Age founder Livia Firth’s #30wears campaign which try to encourage people to think before they spend – in this case encouraging people not to buy anything that they won’t wear a minimum of 30 times – and if the time does come that the item is no longer wanted, it should be high enough quality to be able to pass or sell on, not throw away.”

It comes back to mentality and taking a stand against the belief that cheap fashion is normal.

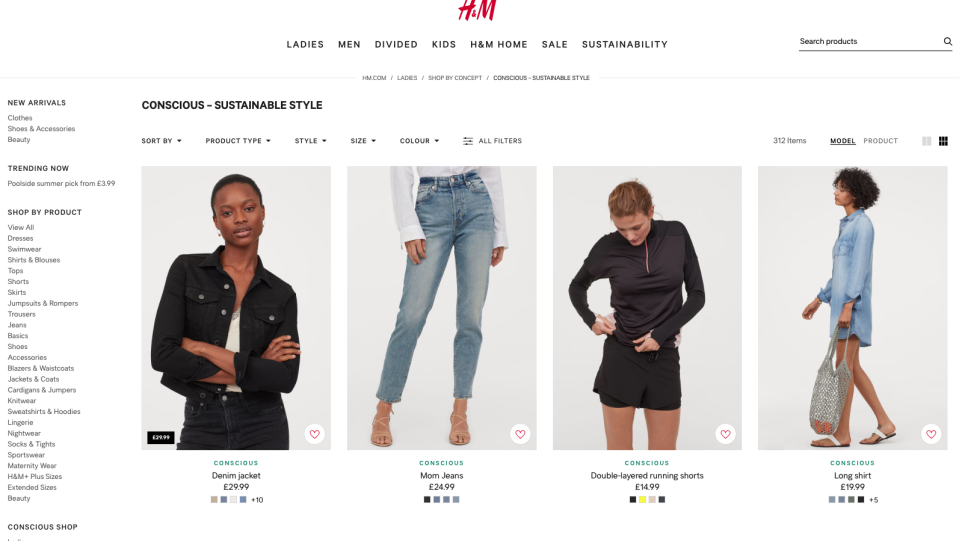

What about brands like H&M’s sustainable campaign?

H&M recently launched its sustainable line dubbed “Conscious - sustainable style”.

“Our Conscious products contain at least 50 per cent recycled materials, organic materials or TENCEL TM Lyocell material – in fact many contain 100 per cent,” H&M explained.

“At H&M we are committed to create great fashion, at the best price in a sustainable way. You can identify our most environmentally sustainable products by looking out for our green Conscious hangtags. Conscious products can be found across all our departments.”

“The business model of fast fashion is built on what is says - fast fashion. So producing huge volumes very cheaply in big turnarounds - so it's a gigantic machine that you can never do sustainably. You can't.”

However, Eco-Age co-founder and creative director Livia Firth said in a conversation in May that she is always suspicious of major fashion retailers’ sustainable lines.

“The business model of fast fashion is built on what is says - fast fashion. So producing huge volumes very cheaply in big turnarounds - so it's a gigantic machine that you can never do sustainably. You can't,” she said.

“It's based on exploitation of labour and you can't do it any other way because they couldn't produce these volumes so cheaply. So that for me is big greenwashing.”

Greenwashing is a term used to describe fashion brands or lines with an eco-conscious bent, but that are a diversion from the business’ larger strategy, which often is completely opposite to the values espoused by the green line.

It can be difficult to know what brands are doing: But Aussies have been warned to steer clear of these 101 fashion brands.

However, Firth acknowledged that there are brands that are beginning to try to change their ways.

“And sometimes change happens very slowly because you are talking about very long supply chains and it doesn't happen overnight. So to start communicating the true values of that company through collections is completely legitimate, as long as that communication is done as part of a wider strategy that you can keep measuring."

GoodOnYou’s Renouf agrees.

Describing it as a balance, he said it’s a good thing that major brands are beginning to engage with consumer expectations but warned against falling into a belief that one line represents the entire brand.

“I think it's great that the larger brands are recognising that there are a substantial number of consumers that want to buy things sustainably and are providing options for them to do that,” he said.

“But I think there's a long way to go.”

What should I look out for?

The GoodOnYou app allows users to enter a brand and see how it ranks, but Baptist World Aid also releases an annual Ethical Fashion report giving the low-down on how Australian brands are performing.

Shoppers can also check out their favourite brands’ websites to see if they are discussing their supply chain responsibilities, and see how open they are about how their clothes are made and how they ensure their workers work in safe workplaces and are paid appropriately. Transparency is key.

But shoppers can also make informed decisions while in store just by looking at the clothing tags.

“It comes down to taking a stand against this perceived need for faster, cheaper, more.”

The tags will indicate where the clothes are made which can offer a hint as to working conditions, as well as what the garments are made of.

“This is something else that brands should be aware of, as lower cost clothing is often made from environmentally impactful materials such as polyester and conventional cotton – what we need to see is more brands converting to materials with a lower environmental impact, considering both their provenance and end of life implications,” Turner said.

Shopping at op shops also helps stem the flow of clothing end up in landfill, while clothing swap and rental sites can also help trend-conscious shoppers keep up with trends without being required to purchase individual items.

If your favourite brand is still falling behind, the best step is to challenge them and ask them about their processes.

“A lot of it comes down to taking a stand against this perceived need for faster, cheaper, more. Discarding the mentality that we need to keep buying to stay on trend or fill a gap in our lives is a really good place to start,” Turner concluded.

Make your money work with Yahoo Finance’s daily newsletter. Sign up here and stay on top of the latest money, news and tech news.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance