Why killing a law that shields tech companies would actually cement the dominance of Facebook, Google, and Twitter

The law that made social media viable in America isn’t getting many Likes these days.

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which grants sites general immunity for their users’ posts, has become enough of a bipartisan punching bag that even Facebook’s (FB) founder is suggesting his industry needs regulation.

“Internet companies should be accountable for enforcing standards on harmful content,” Mark Zuckerberg wrote in a Washington Post op-ed Saturday. The company has since said Zuckerberg meant regulation by industry bodies—but Facebook’s support of an earlier weakening of “CDA 230” still leaves digital-liberties experts alarmed.

In fact, we should all be alarmed. Killing CDA 230 would be a toxic remedy for social media that would help cement the dominance of Facebook, Google (GOOG, GOOGL) and Twitter (TWTR) by making it impossible for newcomers to put up any kind of a challenge. The reason? These giants will have more resources than smaller players to protect themselves if the law is erased.

What the law actually says

The core of CDA 230—“no provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another”—means you can’t successfully sue a site for what somebody posts there. You can only sue the poster.

Sites retain Section 230 immunity if they enforce their own rules, even against constitutionally protected speech they dislike.

For years, people generally accepted its logic: Platforms don’t equate to publishers because forums that let people converse directly aren’t letters-to-the-editor pages that curate their content.

The statute’s only major recent change was last year’s Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, the Facebook-endorsed law targeting social sites which “facilitate the prostitution of another person.” The move caused the likes of Craigslist to close their personals ads, and may have made life more dangerous for sex workers.

Two arguments against 230

Since then, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube have repeatedly flailed in the face of violent extremism. Following attacks on two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, during which one of the shooters live streamed the shooting via Facebook, Rep. Bennie Thompson (D.-Miss.) issued a letter threatening tech CEOs, and the law enabling their services, with undefined new policies from Congress.

“Repeal the legislation that’s responsible for it all,” urged Fortune’s Adam Lashinsky in a March 22 post.

Analyst Tim Bajarin, president of Creative Strategies, agreed in a post Friday, writing, “Not holding Facebook, Twitter and YouTube and others accountable has become a great threat to democracy.”

More recently, Republican politicians have said 230 allows social sites to suppress right-wing voices—despite a lack of evidence of such discrimination.

At the Conservative Political Action Conference in February, Sen. Josh Hawley (R.-Mo.) called CDA 230 a “sweetheart deal” that should be rewritten to prohibit “viewpoint discrimination” by sites.

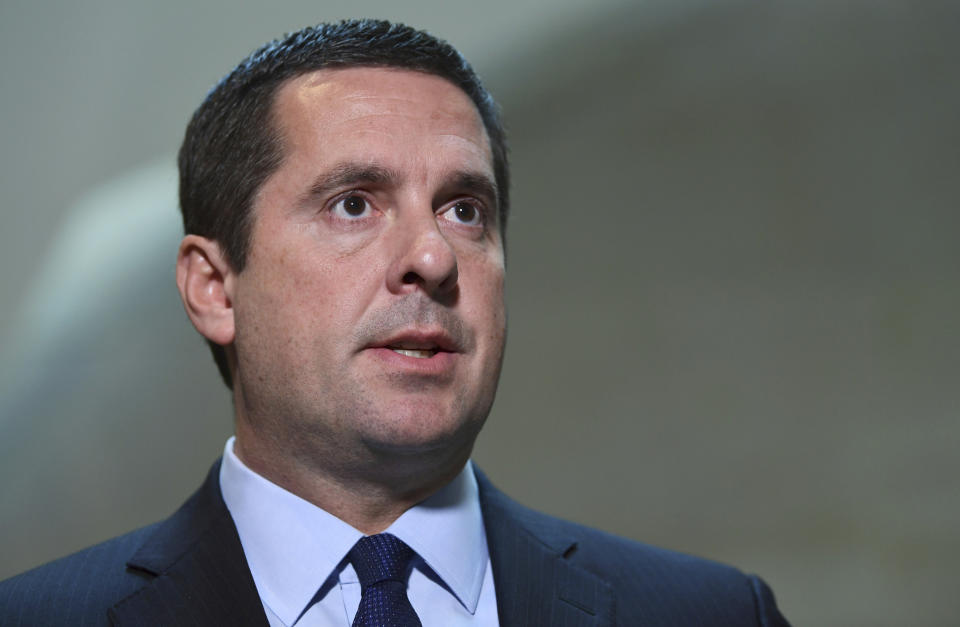

In March, Rep. Devin Nunes (R.-Calif.) filed a $250 million lawsuit against Twitter, Republican political strategist Liz Mair and two anonymous, satirical Twitter accounts called Devin Nunes’ Mom and Devin Nunes’ cow. The complaint alleges that “Twitter contributed materially to the illegal conduct of defamers Mair, Devin Nunes’ Mom and Devin Nunes’ cow.”

Lawsuit fuel

“Most of the people who talk about Section 230 nowadays think that is basically a giveaway,” said Mike Godwin, a fellow with the R Street Institute. But it was actually written to safeguard independent forums, not comfort tech giants: “None of us anticipated that Facebook would exist.”

With other lawyers, Godwin challenged the Communications Decency Act’s sweeping anti-indecency provisions. Those efforts led to a 1997 Supreme Court ruling that those rules violated the First Amendment, which left only Section 230 intact.

Getting rid of 230 wouldn’t erase those free-speech protections, so holding social media to traditional-media standards would not rid the web of hateful content. Remember, the First Amendment protects Nazis too.

Repealing 230 would, however, fuel more lawsuits like Nunes’s—though many Republicans attacking this statute also decry abusive litigation.

“I just don’t think they are thinking through the issue in that way,” said Jesse Blumenthal, who manages tech policy for libertarian entrepreneur Charles Koch’s Seminar Network.

In particular, the entertainment industry would sue sites over alleged copyright infringement by their users—the scenario the European Parliament just endorsed by adopting copyright provisions that will force sites to filter all uploads for copyrighted material or face lawsuits.

Bajarin agreed, emailing that “we would have to have similar filters in place.”

The wrong solution

Facebook is a tempting target—resenting it seems like one of the few things that still unites Democrats and Republicans.

But it’s foolish to make a 230 discussion orbit around Facebook. If that firm’s power is a problem, we can attack it directly by passing a privacy law curbing its ability to monetize our data—or by splitting up the company to recreate competition.

Trashing Section 230, however, probably wouldn’t kill a firm with Facebook’s legal budgets. Others without those resources? Good night and good luck.

More from Rob:

Why these 6 baseball teams won’t let you watch their games online

SXSW 2019: Synthetic sushi, a buggy demo, and other weird gadgets

Email Rob at rob@robpegoraro.com; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance