A day in the life of a neurosurgeon who has operated on thousands

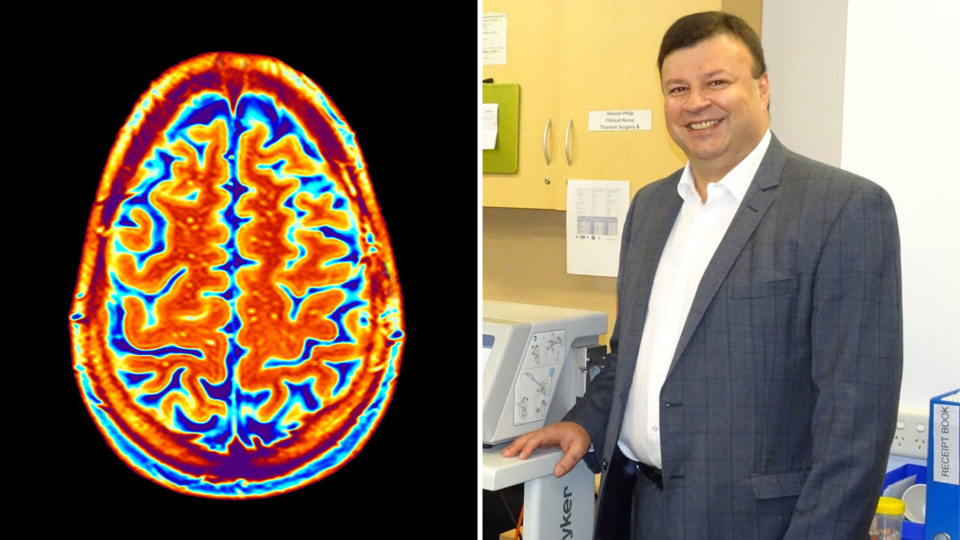

Stephen Santoreneos has operated on so many Australians, he’s actually lost count.

But if the Adelaide neurosurgeon were to guess, he would say 3,000 – although that’s a conservative number. As a qualified neurosurgeon since 2000, that number could be as high as 4,000. And while Santoreneos operates on all ages, his specialty is paediatrics.

Related story: Investor by day, Wonder Woman by night: Inside this thousand-dollar hobby

Related story: ‘Just work your a** off’: A Buddy Holly actor on why career fall-backs aren’t an option

Related story: ‘I’m on a crusade’: This multi-national hotel director will make you want to change careers

“It's one thing dealing with an adult or an elderly patient with disease, but it's a whole different ball game dealing with a baby,” he told Yahoo Finance.

This is why he does what he does

While he quips that his job “keeps him out of trouble”, the reasons why he began, and continues to work as a neurosurgeon are more complex.

“It's probably every medical student's nightmare, neurology.”

As a student, Santoreneos couldn’t help but love the challenge of neurosurgery.

“It's probably every medical student's nightmare, neurology,” he said.

He wanted to face his fears, and figured studying neurology would be the way to do it.

“I didn't want to be just a physician who learns a bit of things and knows about them, and uses medicine to treat things. I wanted to use my hands. I combined that in neurology and surgery.”

Today, his career still gives him the same buzz. The opportunity to fix difficult problems and the quest to push to the next level and keep learning is a potent mix.

Related story: Coffee shop to billion-dollar startup: Lucy Liu shares the Airwallex story

Related story: The coaching sessions critical to my success: PayPal Australia MD

“But as you become more senior, a new part of what keeps you engaged is… engaging with young, enthusiastic people that remind you of yourself when you started. So you are now becoming a teacher and a mentor to this younger population of very enthusiastic young neurosurgeons. And that's another great buzz,” he added.

“Engaging with them, teaching them, watching their skills improving; it's like you watch your kids grow all over again.

“So, for all those reasons, your career as a neurosurgeon will never boring until the day you die.”

While some might suggest it’s the money that makes neurosurgery such an attractive career, Santoreneos is firm: no money can make up for time spent away from your family, your friends and what can become a compromised social life.

“We have some of the most terrible tumours known to mankind, malignant brain tumours that kill patients within a few months, and don't discriminate between age of the patients, or social status of the patients, or families, or anything like that.”

But the benefit is that you watch patients survive.

“It will be unusual to find a neurosurgeon who does neurosurgery for reasons other than the fact that he loves the work that he does.”

What are the challenges of the job?

To state the obvious, neurosurgery isn’t easy. It’s literally brain surgery.

However, Santoreneos said, when you’re on the inside, you realise the belief that neurosurgery is the hardest isn’t always accurate.

“Every subspecialty field will have challenges that make it very unique for the people that do it. So the same can be said for cardiology, or cardiothoracics, the same can be said about the very innovative ways people do orthopaedic surgery now that can reconstruct or lengthen limbs and other things.”

The technical prowess required is far from the biggest challenge.

Instead, it’s the fact that no matter how brilliant a surgeon is, there are just some things that just can’t be fixed.

“We have some of the most terrible tumours known to mankind, malignant brain tumours that kill patients within a few months, and don't discriminate between age of the patients, or social status of the patients, or families, or anything like that.

“It can be quite devastating, irrespective of how successful you are, and how good your x-rays look on your first operation, or how optimistic the patient was at some point, she will succumb to death.”

And there are the technically challenging operations where even after “hours and hours and hours of work” make no difference to the patient, or success comes at the price of some neurological function.

“Every neurosurgeon will go to death with many of those skeletons in his closet.”

The other thing is his focus on paediatrics. This makes things hard.

“You rely incredibly on [your family] to feed you with the different type of attention that you want, which is their love, their support, in order to be able to cope with the demands of the other side.”

As he said, it’s a whole different ball game when there’s a baby involved.

“You watch the family who have invested so much love and so much heart into this poor soul, and if something doesn't go well, or they have a disease that you can't do much about… it can be very, very difficult.”

How do you destress?

Appreciating the successes and the lives saved or improved help Santoreneos.

But it’s also important to have a personality that deals well with stress to begin with.

“You have to have a personality that can often disengage, stand back, and look at the reality of this rather than get involved in the normal complexity of each individual.

“So you have to have a perspective where you can sit back and logically analyse things, rather than become overwhelmed by every individual event.”

You also need to have an “extraordinarily supportive group of people around you”.

That’s your colleagues, your friends and your family.

“You rely incredibly on them to feed you with the different type of attention that you want, which is their love, their support, in order to be able to cope with the demands of the other side.”

A supportive family is absolutely critical. After all, Santoreneos said, they don’t give up their needs just because you have an incredibly demanding job.

Related story: How to tell your boss you need a mental health day

Related story: Working one day a week is enough to keep our mental health in check

Related story: 5 work perks Australians want most in 2019

“You know, whatever they're doing, it's altruistic. They're doing it because they love you. They're doing it because they think you are a valuable member of their pride. And they're willing to put up with all those things they're not going to get from you, because you're engaged otherwise in a very intense profession.”

The neurosurgeon also likes to literally escape the pressure of the job by heading overseas.

He’ll take his family far enough away once a year that he can completely avoid the otherwise inevitable, “I know you're on holidays, but please come in and look at this,” phone calls.

“And hopefully when you come back, you're rejuvenated.”

So, what does an average day look like?

At work by 7am most mornings, he’ll generally start the day with some form of a ward round at one of the hospitals he works at. Come 8:30am, there’ll be an academic meeting where cases or new research is discussed. Then it’s perhaps another ward round, before going to theatre.

“The rest of the day will be split up between an operating room where you operate on patients, and depending on the complexity of the cases, there may be one case that you deal with for the rest of the day, and sometimes the night, or early hours of the next day,” he said.

“Or it may be a number of cases if there are short, just two or three or more. In other days, instead of going to theatre, you will go to a clinic where you will have a clinic seeing patients all day.”

On top of that, there’s the administration.

“It's always a very busy life, where it starts at 7:00 in the morning, and it will often finish on a good day at 7:00, 7:30 at night.”

And on some days, it can be midnight or beyond.

Make your money work with Yahoo Finance’s daily newsletter. Sign up here and stay on top of the latest money, news and tech news.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance