A look at fan rage from 1994 MLB strike, and those who never really came back

I don’t remember the year that there was no World Series. At age 4, I was old enough to profess that I loved baseball but young enough to not actually notice when it went away. I probably didn’t know what the postseason was and you couldn’t have explained labor strife to me if you tried.

The whole thing entered my consciousness as a fully contextualized historical anecdote sometime later. In retrospect, the story is complex. On the 25th anniversary, we look back at it with renewed resonance and wary relevance. None of which can quite capture what it feels like for there to suddenly be no baseball where baseball had just been, where you expect it to be. Even if the looming work stoppage that threatens from beyond the end of the current collective-bargaining agreement comes to pass, the experience of living through it sentiently will probably be dominated by the particularities — we’re likely looking at a preseason lockout if anything — and my professional responsibility to follow along with all the prognostication.

The 1994 Major League Baseball strike was about a bunch of things — like a salary cap and a strong union, Bud Selig and rising television revenue. Its impact on those factors, on the factions within the game that have continued to jockey with one another for power and money, is the strike’s legacy.

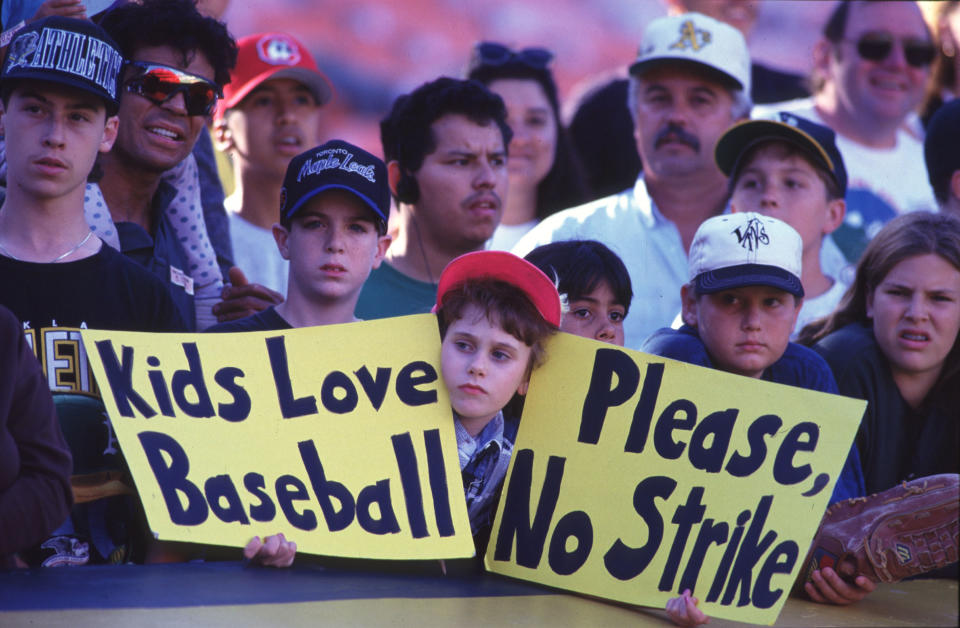

It was never about the fans, but still I want to understand what it felt like for those who served as leverage in that fight — because in some cases, the impact was long-lasting for them, too. How they felt, it seems, was angry.

Media calls for fan boycott

There is a dramatic selection bias inherent in treating contemporary op-eds like reliable barometers of public sentiment but the point is, in the late summer of ’94, a few newspaper writers called on fans to stop watching baseball in the wake of the strike.

“Fans must boycott if games return,” Bob Raissman wrote in the New York Daily News on Sept. 9. “It’s not about a game anymore,” he opined, calling on fans to “send these self-serving creeps a message.”

When Selig announced in mid-September that the remainder of the season, including the World Series, would be canceled, Dave Anderson wrote in the New York Times that people no longer cared about baseball.

“And some might never care again.”

A month later, the Washington Post’s Kevin McManus took a semi-serious look at how a boycott could happen. He imagined a single-game symbolic avoidance on the upcoming Opening Day (“whenever that may be”), reaching out to Ken Burns, labor professors, and PR professionals to gauge the feasibility of getting fans around the country on board with such a proposal. Although he concluded that the logistics were likely prohibitive, the fans he spoke to were enthused at the suggestion.

“Playing in front of an empty stadium would give players the sense of loss that a lot of fans feel, myself included,” an Orioles fan was quoted as saying.

As interviewees in op-eds around the country, some fans went even further. The Arizona Republic spoke to a Dodgers fan who said “he likely will stop watching them, even on television.” The Courier-Journal in Louisville, Kentucky spoke to a dozen fans who complained about reprehensible greed or claimed that they would play for free before concluding that, “The only way to let the players and owners know how we feel is to have the fans strike next year.”

“I don’t care if they ever play anymore,” a fan named Evelyn Terry said.

D.L. Stewart, a columnist at the Daytona Daily News, tried to call their bluff.

“If fans really think the stupid, greedy owners are making too much money, there is a simple answer. Stop buying tickets. If the fans really think the stupid, greedy players are making too much money, there is a simple answer. Stop buying tickets,” he wrote.

“It’s never going to happen, of course. Fans talk about how they’re never going to go to another game because it’s nothing but a big business now and not the innocent pastime it used to be when they were kids.

But they’ll go.”

A community of fans who gave it up

So did they go back? Not all once, no. The average attendance dropped from over 31,000 per game to just above 25,000 between 1994 and 1995. It has dropped again in recent years for a number of heavily scrutinized reasons but there was a bounce back in between. And besides, that’s not quite what I mean. It won’t show up in the averages or the trend analysis, but I wanted to know: Did any of the disgruntled fans keep their word? Did anyone give up baseball for good?

The internet is probably not the ideal place to canvass for people who are necessarily of a certain age to remember having strong opinions 25 years ago. I figured if they’re anywhere, though, they’re on Facebook — and concentrated in a group some 29,000-members strong called “Baseball 1857 to 1993.”

The name, as it turned out, was a little bit misleading for my purposes. The group acknowledges baseball played only before the 1994 season not because it was strike-shortened — but because it featured six divisions.

(“Baseball has recovered from the 1994 strike but I feel it will NEVER recover from all the changes adopted, starting in 1994. Such as going from 4 teams in postseason play to 6 teams (then 8 and now a whopping 10). Wild-card teams, interleague play also,” moderator Richard Burns explained to me — which is at once illuminating and confounding.)

I inquired anyway. And was met with droves of commenters disagreeing amongst themselves about whether “real” baseball fans are those who stuck by the game or those who were disillusioned by the strike. For some people, it was the beginning of an end marked by increasing rule changes and marred by the steroid era. For others, it was a low point, the PED-fueled home-run race brought them back, and by now they’re bigger fans than ever. In other words: an unhelpful expanse as broad as you could reasonably expect to find within the population of a single Facebook group.

Eventually, I found a few people, from within the group and elsewhere, who hold the kind of grudge many of us can only aspire to.

“I am a man of my word. Believe me, when the Yanks were winning it was tough not to watch, but I left the game and I wasn't about to be a hypocrite,” explained Carl G. Dalbon, who was 41 in 1994. “As far as I'm concerned, they can have the game and all that goes with it. I've come to do without it for [25] years even though I know I've missed some incredible Yankee moments. I don't regret my decision in any way.”

Dalbon has a commitment that’s tough to match among casual fans for whom total abstinence is gainless sacrifice. But there’s still a sense of lingering resentment that manifests as a series of boundaries and distancing tactics.

“My thought was, they didn’t finish the season so why invest my time because it could happen again,” explained Mike Lee, who was 32 at the time. “I still watched a lot of college and high school games. I love the sport.”

In the past few years, he’s started watching again a little, but “I’ve never gone back to following MLB as I did before the strike.”

“After the [World Series] was cancelled, and the ‘replacement sham,’ I changed. I was barely paying attention to the Reds, I guess the reality is I held animosity toward all, the owner for certain. I would occasionally focus on a Reds game if I saw it on ESPN, but even listening to the Reds on the radio faded,” explained Jim Doty, who was in his early 20s during the strike.

“I still love the game, but I am not buying baseball cards, or reading any pay publications or any pay-per-view to watch it,” he said. “I won’t buy big expensive item souvenirs; and if I go to a game I will only buy the cheap-seat tickets whereas I used to go and want to be as close to the field as I could afford to get.”

Then there were the people for whom MLB was not quite an employer but a source of business. Jonathan Holomany, 28 years old in ’94, owned three baseball memorabilia shops at the time. He gambled on guys he thought would blow up by buying rookies in bulk, and his 15,000 or so Ken Griffey Jr. cards were about to appreciate real fast if the Mariners star broke the single-season home run record. Then the strike happened. He admits the business was already floundering so he packed up a semi-truck to sell everything at the annual convention in Houston two weeks into the work stoppage, but no one was buying baseball cards that year and it was clear that Griffey wouldn’t get the chance to catch Roger Maris.

“I probably lost $150,000 in that show alone just because of the strike.”

It doesn’t matter how accurate that calculation really is, Holomany soured on the league for good. “I have not bought a single anything that’s officially licensed by Major League Baseball,” he said. When he does deal in baseball cards now, they’re all pre-WWII.

The prevailing sentiment among contemporary reports (and the comment section of modern labor stories) would lead you to believe that the type of people who were mad enough to cut off their nose to spite their face are the type of people who blame players for expecting any sort of compensation for a “child’s game.” And there was certainly some of that.

“To think that grown men would allow that to happen with a game that most of us would have played for free was unconscionable,” Dalbon said.

And yet, I was surprised that when asked to place blame, people predominantly blamed the owners — and Selig.

There’s a favorite villain in all of this

“The owners without question were responsible for the strike, but particularly Bud Selig who was a crony lapdog to the owners,” Doty said.

“I think both owners and players were to blame but ultimately the owners bore most of the responsibility,” Lee said.

“The owners are always the a------s that have indentured servants,” Holomany said.

Even Dalbon: “Selig angered me the most. It sickens me that he is in the [Hall of Fame] after the strike, a tie in an All-Star game and his unabashed laissez-faire approach to steroid usage.”

That’s the thing about the real baseball boycotters: It seems like it was never really about the strike. At least not just about the strike. Everyone I encountered had a list of grievances that has little to do with labor relations:

Wild cards, interleague play, commercials, replay, swinging for the fences, reliever usage. Not enough strategy, not enough bunting, not enough hitting behind the runner, not enough autograph signing. Fewer steals, fewer complete games, fewer deep pitching outings. The games are too long. The games are too expensive. The games aren't kid-friendly. Homers, walks and strikeouts.

This is not to say that the strike didn’t matter; or that the dissonance of a summer without baseball and the shattered sense that the game was bigger than the business didn’t dispel some of the magic. It did, and fans were left feeling like suckers upon realizing that they didn’t even have a seat at the table. The game was changing around them — it still is, it always was — from something they loved to something else and there was nothing they could do or say to stop it. All they could do was look away.

There’s a little bit of that in every adult sports fan, the knowledge that no matter how much you care, the only power you really have is to stop caring. I respect, then, when people choose to exercise that power. But it’s remarkable how often we choose not to.

More from Yahoo Sports:

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance