Why we don't own a home anymore

House prices are NOT the main source of falling home ownership rates in Australia.

This is an inconvenient fact that the peddlers of the myth of housing bubbles, booming house prices and inevitable price crashes refuse to acknowledge. They almost always cite rising prices as the reason why fewer people are stepping into the world of home ownership. They seldom, if ever, look at other non-financial factors that are influential in reducing home ownership rates, especially for the younger age cohorts.

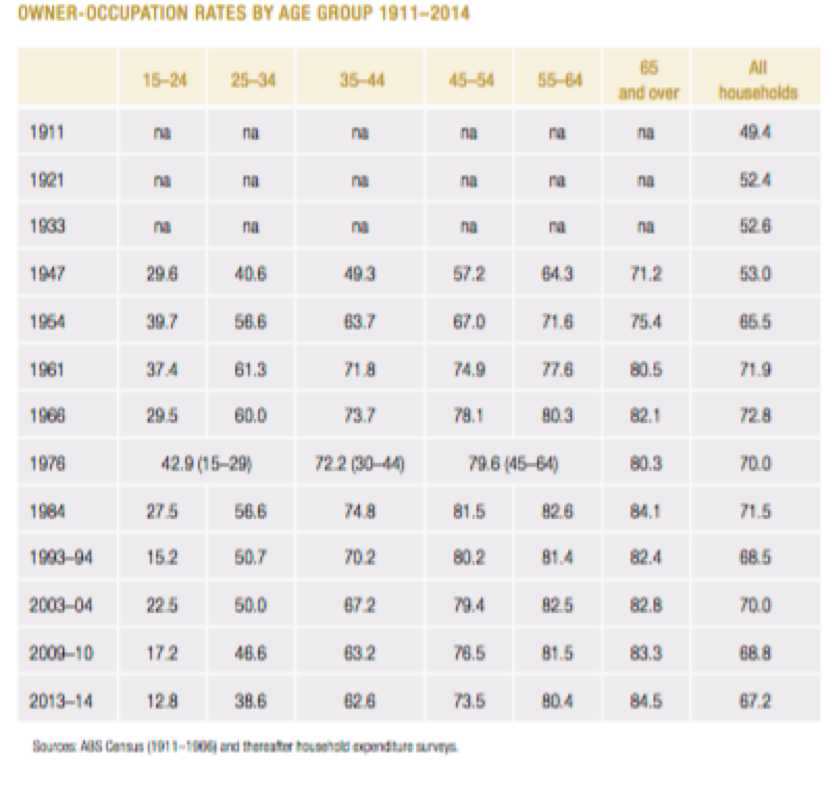

In a paper published this week by the Committee for the Economic Development of Australia ( http://adminpanel.ceda.com.au/FOLDERS/Service/Files/Documents/36002~HousingAustraliaFinal_Flipsnack.pdf ), there was a striking table which showed home ownership rates by age cohort since the 1950s. It was a fascinating table that is open to scrutiny and interpretation.

Also read: Is Sydney property closer to crash bang?

The table is reproduced here:

Perhaps the most striking change in home ownership rates is for the 15-24 year olds. Within the age cohort, there has been a staggering shift in home ownerships rates which has fallen from a phenomenal 39.7 per cent in 1954. Since that peak, in almost every subsequent time period, the ownership rate has declined and according to the latest data for 2013, it is at a historical low of just 12.8 per cent.

This 60 year period captures periods where house prices were very low and prices were falling, periods where price growth was strong and times when access to mortgages was severely curtailed by rules and regulations.

Even when house prices were flat or falling in real terms, ownership rates fell sharply. The CEDA report has some excellent data on long run house price levels to confirm this fact.

You don’t have to be John Maynard Keynes to work out that house prices, clearly, were not the driver of ownership rates.

Back in the 1950s, the Year 12 school retention rates were limited to less than half the population and university was a rarity with just 2 per cent of school leavers going on to tertiary education.

Also read: Why Beyoncé and Jay Z $65m mortgage is a good idea

As people got into paid work at age 15 or16, by the time they turned 25, a decade in the workforce had presented an opportunity to save some money and to get into the housing market.

Progressively over the last 60 years, high school year 12 retention rates have risen to nearly 90 per cent, as has the proportion of young people going to university. These changes are dramatic on their impact on home ownership rates.

This alone would account for a significant proportion of the drop in home ownership rates in that cohort. After all, ask any 17 year old today how difficult it is to save for a house when you are studying for HSC English or geography. A 21 year old university study as they mull the possibility of doing an honours year clearly is postponing their house purchasing options but building skills and future income at a cost of low income today.

No wonder home ownership rates in that cohort have fallen precipitously.

And of course, those young people of the 1950s and 1960s with a poor education, but lucky enough to buy a house, are now in the 75 year olds who many of today’s well educated and articulate millenials loath and despite because of their home ownership status and accumulated wealth.

As Reserve Bank of Australia research on the matter of home ownership rates has found, the decline in home ownership rates over many decades is also linked to social and demographic factors. It notes a latter age of “household formation” as a factor. That is a significant rise in the age of getting married and having a dual income (including for managing the household) – has worked against buying at a younger age.

The RBA has also noted that with a rise in divorce rates, especially since the 1970s, ownership rates have fallen. Divorce often results in a dispersion of what was a higher two-household incomes in one house to two lesser separate incomes in two houses.

Simply put, there is much more to the home ownership issue than house prices.

For some in the community, rising house prices and the resulting difficulty in scraping together a decent deposit is undoubtedly an issue. Changes in spending patterns and an accumulation of university debt are other factors. But overall home ownerships rates are falling for many reasons, many to do with social changes that cannot be influenced by policy changes.

After all, no one is suggesting we get kids to leave school at 15 so they can get a job, and people getting married is lesser proportions and in later years. All of which undermines the home ownership rates.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance